Deforestation, human-animal conflict and global experiences

Part 3

By Lionel Bopage

The global crisis

Deforestation and human-animal conflict have become dangerously intertwined as natural habitats shrink. Wildlife is continuously forced closer to human settlements. The numbers indicate a sobering picture. In 2024, the world lost 16.6 million acres of tropical primary rainforest, at an alarming rate of 4 to 5 cricket fields a minute.

By the end of 2025, the main drivers of this destruction became crystal clear. Commercial agriculture, particularly for the production of commodities like soy, palm oil, and cattle, leads the devastation. Indigenous communities sustainably manage 25 to 28 per cent of the world’s land. They are forced to migrate due to deforestation. It results in cultural erosion and heightened poverty. Tragically, they also account for 40 per cent of environmental defenders killed globally. They are the people murdered for trying to protect the forests that sustain us all.

Over 1.6 billion people rely directly on forest resources. The loss of primary forests jeopardises medicinal plants and traditional food sources. It leads to malnutrition and health crises in communities that have depended on these ecosystems for generations.

Ecological chain reaction

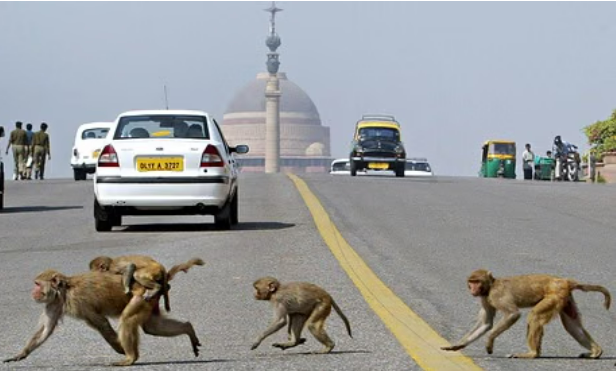

Photo Credit: Reuters

Deforestation disrupts ecological balance in devastating ways. As wildlife corridors are severed, animals are forced into human territories searching for food and water. This results in crop raiding and livestock predation. This heightened interaction raises the risk of zoonotic disease outbreaks[i]. Forests harbour around two-thirds of the world’s species. Their destruction pushes nearly half of endangered mammals toward extinction.

The patterns vary by region, but the underlying theme remains consistent. In Colombia, illegal clearing for coca[ii] cultivation and cattle pasture surged amid the power vacuum following peace treaties. In Brazil, agribusiness expansion accounts for nearly 80 per cent of Amazon deforestation. Due to development projects, such as roads, hydroelectric dams, and mining operations, the clearing of remote forest areas continues. Climate-induced fires, exacerbated by extreme droughts, have contributed significantly to forest loss in Brazil and Bolivia. Armed conflicts in various regions have accelerated deforestation rates even further[iii].

India’s wildlife crisis: A regional warning

Photo Credit: Getty Images

Close to Sri Lanka, India faces a critical wildlife crisis. Rampant deforestation and habitat fragmentation drive it. This intensifies human-animal conflicts, particularly with elephants and monkeys. With less than 20 per cent of original forest cover remaining, wild animals are increasingly forced into human-dominated areas searching for food.

The statistics are grim. Elephants now inhabit merely 3.5 per cent of their historical range. Between 2011 and 2021, approximately 3,200 people and 1,150 elephants lost their lives due to conflicts, particularly in high-risk states like Odisha, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Karnataka. In Kerala[iv] alone, elephants contributed to 103 of the 344 human-wildlife conflict fatalities from 2021 to 2025.

The key factor exacerbating these conflicts is the fragmentation of migratory corridors. The fragmentation is caused by linear infrastructure and agricultural development, alongside climate change and invasive species depleting natural resources. Electrocution has emerged as the primary cause of elephant deaths in conflict zones. Train accidents and retaliatory poisoning follow close behind.

Monkey conflicts present another dimension of this crisis. Monkey species such as Rhesus macaques and Langurs[v] cause considerable agricultural losses in states like Telangana and Himachal Pradesh. Their presence in urban areas, especially New Delhi, poses safety threats, with numerous attacks reported annually. Cultural reverence for these animals encourages their feeding and aggregation in human habitats, despite official prohibitions aimed at managing their populations.

Sri Lanka’s escalating crisis

Photo Credit: Getty Images

Sri Lanka currently grapples with a critical environmental and social crisis stemming from severe deforestation and escalating human-animal conflicts. The nation’s forest cover has plummeted from 84 per cent in 1881 to about 29.7 per cent in recent decades. This catastrophic loss stems primarily from agricultural expansion, notably tea and coffee plantations, infrastructure development, including the Southern Expressway, and urbanisation. All of these have fragmented natural habitats.

The conflict with elephants has reached alarming levels. Sri Lanka now records the highest global elephant mortality rate. In 2025, approximately 408 elephants and 149 humans lost their lives due to these conflicts. The conflicts were largely driven by habitat fragmentation from agricultural and infrastructure projects like the Mattala Airport. This forced elephants into human territories searching for food. The main causes of elephant deaths include gunshots, electrocution, and train accidents, alongside injuries from improvised explosives known as “hakka patas.”

Conflicts involving Toque macaques and peacocks have also intensified. Macaques increasingly raid crops and households, leading to substantial economic losses. This is fuelled by habitat destruction and improper waste disposal that lures them into human settings.

The rising human-peacock conflict has emerged as a significant ecological and agricultural issue due to deforestation and habitat alteration. This has facilitated peacock migrations from traditional habitats to populated areas. Peacocks, while culturally significant, have become major agricultural pests, damaging crops and disrupting local ecosystems. Infrastructure expansion has aggravated the risks of bird strikes in aviation involving peacocks.

International solutions taking shape

Photo Credit: Getty Images

In 2025, strategies for addressing deforestation and human-animal conflict began emphasising the integration of nature-based climate actions with socio-economic empowerment.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework represents a major initiative, with 190 nations committing to protect 30 per cent of the world’s land and sea by 2030. The WHO Pandemic Agreement was adopted as a legally binding treaty in May 2025. It aims to mitigate “spillover” drivers linked to deforestation and high-risk wildlife trade, addressing zoonotic disease prevention at the source.

The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) established a framework requiring large operators to comply with it by December 2026. In Brazil, a significant multibillion-dollar initiative rewards countries for maintaining forest ecosystems. This is done by funnelling support directly to Indigenous Peoples and local communities. The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) similarly incentivises forest conservation through financial channels directed to local communities.

Countries like Barbados are innovating with “debt-for-climate-resilience” swaps. It offers debt restructuring in exchange for commitments to local conservation efforts. Market-based financing is evolving from basic grants to “impact investing” focused on species protection and conservation outcomes.

Mitigating Human-Animal Conflict

Landscape-level management strategies are evolving from traditional protectionist approaches to coexistence models. India’s “Wildlife Week 2025” theme, “Human–Wildlife Coexistence,” features projects like Tigers Outside Tiger Reserves (TOTR), managing wildlife across broader landscapes rather than confined parks.

In South Africa, successful approaches included a 2025 initiative to relocate a threatened elephant herd to a safer reserve. It utilised collaring technology, immune-contraceptives, and community monitoring. High-tech solutions are evident in Kenya, where AI-enabled thermal cameras combat rhino poaching. India employs M-STrIPES[vi] for real-time tiger monitoring.

Legal recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights emerges as a cost-effective conservation strategy, as they manage 80 per cent of global biodiversity. Organisations like Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) are creating standardised traceability systems for beef and leather to prevent deforestation-linked products from entering markets.

In India, notable policy changes in 2025 included a Maharashtra directive mandating the release of trapped monkeys at least 10 kilometres from human habitation. Farmers are being encouraged to adopt alternative crops like ginger, turmeric, or chilli, which are less appealing to monkeys. Technological innovations like the AI-based “Hathi Mitra App” in Chhattisgarh and sensor alerts in Uttarakhand alert villagers regarding animal movements.

States like Kerala and Uttar Pradesh have classified human-wildlife conflict as a “state-specific disaster,” streamlining compensation and disaster management funding. Physical barriers such as solar-powered electric fences and bio-fencing techniques have been enhanced to deter animals non-lethally. Providing research-informed strategies for the mitigation of human-animal conflict is the aim of the Centre of Excellence for Human-Wildlife Conflict Management.

Conclusion: A global challenge requiring global solutions

The intertwined crises of deforestation and human-animal conflict represent one of the most pressing challenges of our time. From the Amazon to India to Sri Lanka, the pattern of the conflict is disturbingly consistent. As forests disappear, wildlife and humans are forced into closer proximity, creating conflicts that are deadly for both.

The international community has begun responding with ambitious policy frameworks like the “30×30 Initiative”[vii] and the WHO Pandemic Agreement. These represent recognition that forest conservation and wildlife protection are not merely environmental issues. They are matters of human survival, economic stability, and global health security.

Yet policy frameworks alone are insufficient. The solutions emerging from the ground, community-based management, Indigenous rights recognition, technological innovations for early warning, and economic incentives for conservation show what is possible when political will meets practical action.

The key lesson from examining these global patterns is that human-animal conflict is not primarily a wildlife problem. It is a land-use problem, a development problem, and ultimately a human problem. Animals are simply responding to habitat loss by seeking food and territory wherever they can find it. The solution lies not only in controlling wildlife populations but in restoring habitats, maintaining corridors, and fundamentally rethinking how human development can coexist with the natural systems that sustain all life.

For Sri Lanka, observing these international trends offers both warning and hope. The warning is that without decisive action, conflicts will continue escalating as forests shrink further. The hope is that proven solutions exist, from community-based fence management to habitat restoration and use of AI-enabled early warning systems. The question is whether Sri Lanka will learn lessons from global experience and implement these solutions before more lives, both human and animal, are lost.

[i] This refers to diseases that are naturally spread from animals to people, such as pets, livestock, and wildlife. Pathogens cause transmissions and include bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi. The diseases can spread through direct contact, contaminated food or water, or the environment, posing serious risks to public health and impacting millions of people worldwide.

[ii] Coca is primarily associated with the leaves of a family of South American plants that contain cocaine. These leaves have been traditionally employed for mild stimulation and as a source of illicit cocaine.

[iii] Through the collapse of governance and dependence on natural resources for survival and war financing, armed conflicts exacerbate deforestation. Armed groups exploit resources like timber and minerals, causing unregulated deforestation and environmental pollution. Local forests are strained by refugee settlements that are a result of conflict, while illegal logging and mining continue to thrive without regulation. Military tactics often involve clearing forests for strategic purposes. Rates of deforestation rise after a war, as farming needs to grow when people return home. These changes exacerbate climate change and biodiversity loss and marks a reversal of sustainable development.

[iv] Kerala’s progressive government, led by the Left Democratic Front (LDF), was re-elected in 2021. It operates under India’s quasi, or semi-federal system, which is more tilted towards a unitary form of government. It contains features of both a federal and a unitary system. Article 1 of the Indian Constitution states that India, or Bharat, will be a union of states.

[v] In Sri Lanka, the term “Rilaw” (රිළව්) specifically refers to the Toque macaque (Macaca sinica), distinguishable from the Rhesus macaque found in India. The name “rhesus” is thought to be rooted in mythology. Additionally, Asian leaf-eating monkeys, known as Langur, are part of the subfamily Colobinae within the Old World monkey family. In Sri Lanka, specific species include the tufted grey langur, referred to as “Heli wandura” (හැලි වඳුරා) or “Alu wandura” (අළු වඳුරා), and the purple-faced langur, known as “Kalu wandura” (කළු වඳුරා).

[vi] M-STrIPES is India’s critical mobile-based system (Monitoring System for Tigers – Intensive Protection and Ecological Status) for monitoring tigers and habitat in tiger reserves, using GPS/GIS to track patrols and wildlife data for conservation.

[vii] The “30×30 Initiative” encompasses two significant global campaigns to safeguard 30 per cent of land and oceans, and to enhance women’s representation in law enforcement to 30 per cent by 2030. These initiatives are associated with wider international agreements, notably the Kunming-Montreal Framework.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of this publication

Leave a comment