The world must not forget that while Sri Lanka’s war had many villains, one of the earliest, most cunning, and most cruel came wearing a uniform not of the lion, but of the Ashoka chakra.

By Luxman Aravind

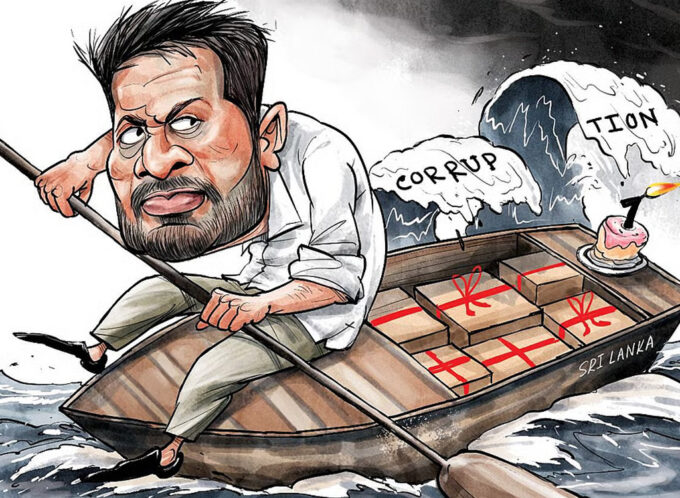

When history is written by victors and erased by allies, truth becomes the first casualty. Nowhere is this more evident than in the brutal, unspoken legacy of India’s involvement in Sri Lanka’s civil conflict. Long before Colombo’s skyline began to shimmer with high-rises and foreign flags, this island was wounded—deeply, deliberately, and devastatingly—by the very neighbour that styled itself as South Asia’s elder brother. India did not merely interfere in Sri Lanka’s affairs; it scorched its soil, brutalised its people, and left behind an open wound that festers even now, decades later. The dream of development in Sri Lanka is not just delayed by internal misrule or ethnic distrust. It is haunted by the Indian footprint, unrepentant and unacknowledged.

It began with whispers, long before guns arrived. There was a rumour, persistent and oddly personal, that Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, was offended when Ceylon’s independence date was announced. He wanted India’s freedom to come first, even if only by a day. Whether apocryphal or not, the story captures a truth—India has always looked at Sri Lanka not as a neighbour, but as a younger sibling to be guided, managed, and if needed, disciplined. This psychological superiority would one day translate into one of the bloodiest foreign interventions South Asia has ever seen.

In the early 1980s, as Sri Lanka’s ethnic tensions exploded into war, India played a double game worthy of empires. While calling for peace in public, its intelligence agency—RAW—was training, arming and financing Tamil militant groups, particularly the LTTE. Camps were set up in Tamil Nadu; fighters were flown to Delhi; weapons crossed borders with official blessings. India did not want a strong, independent Sri Lanka aligning with Western or Chinese interests. Destabilising the island, even at the cost of Tamil civilian lives, served a deeper strategic goal. For India, Eelam was never about justice. It was leverage.

But the snake turned on its keeper. When the LTTE refused to obey Indian diktats, Delhi panicked. The Indo-Sri Lanka Accord of 1987, signed without consulting the Tamil people, was meant to impose a “solution” from above. The Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) arrived with smiling officers and peace slogans. But it was no peacekeeping. It was war—vicious, intimate, and unaccountable.

Within weeks, the IPKF turned its guns on the very Tamil civilians it claimed to protect. Villages in Jaffna, Batticaloa, Trincomalee were bombarded. Arbitrary detentions swept up thousands of young men. Torture centres were set up in school buildings. Women were raped, their dignity crushed not by foreign invaders but by a neighbour speaking their language. In October 1987, Indian troops stormed the Jaffna Teaching Hospital and gunned down doctors, nurses, patients—over 60 people slaughtered in cold blood. The Indian state called it “an unfortunate misunderstanding.” The people of Jaffna called it what it was: murder.

One mother, whose 14-year-old son was abducted and shot by the IPKF, said through tears, “We thought India came to save us. Instead, they came to bury us.” Her voice never made it to New Delhi. No Indian court ever tried a soldier for war crimes in Sri Lanka. No government ever offered reparations to the victims of rape, massacre or torture. India walked away in 1990, not defeated, but disinterested. The war had served its purpose. Sri Lanka was destabilised. The Tamil movement was fractured. Delhi had made its point.

But the wound it left behind did not heal. In Tamil areas, the memory of IPKF brutality became indistinguishable from the pain inflicted by the Sri Lankan state. For the Tamils, it was betrayal piled on betrayal. For the Sinhala majority, it reinforced the suspicion that India would never respect Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. In the end, nobody won. The war continued for two more decades. Hundreds of thousands died. And India watched, wagging its finger at Colombo while pretending to be a neutral observer. The hypocrisy was astounding.

Even today, India remains allergic to truth on this matter. The archives of its Sri Lankan operations remain classified. No prime minister has visited Jaffna to apologise. No Tamil rape survivor has received compensation. The Indian press remains largely silent, preferring to romanticise the IPKF as misunderstood heroes. This is not silence born of shame. It is silence born of strategy. Acknowledging the crimes of the IPKF would mean dismantling the carefully curated myth of India as the region’s moral superpower.

But what is most unforgivable is not just what India did, but what it left behind. The IPKF crushed not only the LTTE’s will but also the soul of Tamil civil society. Journalists, academics, priests—those who tried to speak out—were targeted, interrogated, sometimes killed. One Catholic priest in Batticaloa who documented IPKF atrocities was found dead under suspicious circumstances. His diary disappeared. His name was never spoken again.

The LTTE, already brutal, became more ruthless after facing India’s betrayal. Civilian Tamils, squeezed between a genocidal Sri Lankan state and a vengeful LTTE, had no refuge. And India, the original arsonist, now paraded itself as a firefighter. It became a stakeholder in every “peace process” while evading every question about its role in starting the fire.

India’s defenders often say, “It was a complicated time.” Or, “It was an internal matter gone wrong.” But there is nothing complicated about rape. Nothing ambiguous about shooting patients in a hospital. Nothing diplomatic about torturing teenagers in schoolyards. These are not footnotes of history. They are crimes. And crimes demand justice.

Sri Lanka today dreams of highways and foreign investments. It wants to join the league of emerging Asian economies. But no nation can build skyscrapers on a graveyard of unacknowledged pain. Development is not just GDP and infrastructure. It is dignity. And so long as the crimes of the IPKF remain buried under the asphalt of Indian ambition, this island will limp, not rise.

In Mullaitivu, where the war ended in fire and silence, a Tamil grandmother still lights a candle every year in memory of her daughter, raped and killed by Indian soldiers in 1988. She does not speak English. She has never heard of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord. But she knows what truth feels like. “They came with smiles,” she said. “They left with our daughters.”

And so, the wound remains. Because India never said sorry. Because it never paid damages. Because it never looked the victims in the eye. Nehru may have wanted independence a day before Sri Lanka. But in the end, it was not a day that separated the two nations. It was a betrayal deep enough to last generations.

*The article was originally published on Sri Lanka Guardian.

Leave a comment