A capital question

By Chayu Damsinghe

(This piece is written as part of a potential multi-part series exploring Colombo as an economic region, arguably distinct from the rest of Sri Lanka. There’s obviously a lot of history behind the idea, but this one is to take a relatively simple approach to “measure” how “rich” Colombo potentially could be. The methods I’m using here are not those I personally find very credible, but as an initial exploration, I am starting here nevertheless).

There’s no question that Colombo is richer than the rest of Sri Lanka. Most Sri Lankans (and many others who’ve listened to a Sri Lankan) have probably also heard the apocryphal story of Lee Kwan Yew, Singapore, and Colombo. But how rich is Colombo really? Is it potentially, a rich city in and of itself?

Before we start – What is Colombo?

One question here is what “Colombo” really is. Officially, that would be the Colombo Municipal Council. But this comes against the fact that Sri Lanka’s urban definitions are really weak – and has resulted in many “urban” areas being classified as rural. For example, Wattala, Ja-Ela, Gampaha are all classified as rural areas, purely due to the fact that they’re under Pradeshiya Sabha, as opposed to Municipal or Urban councils. There are other definitions thereby, that we can take, but defining what “Colombo” is will probably still be quite nebulous. Is it based on governance? Economic connectivity? Distance? All of these? None of these?

In order to move past this, and since we’re not really aiming for some precise number on Colombo itself, lets take a few approaches. Lets move from the biggest definitions we can and move in, and see what it implies on Colombo itself. That is, let’s first look at the Western Province, the Old Colombo District, the Colombo District, and one additional external definition. Despite my disagreements with GDP, and particularly GDP in PPP terms, I’ll still use this as a comparative to place each of these different “Colombo”s in a global context – in per capita terms of course.

How rich is the Western Province or the “Colombo Metropolitan Region”?

There are at least some, and some of these being semi-official, definitions that take the entire Western Province as the “Colombo Metropolitan Region”. So let’s start there. Thankfully, provincial GDP is something we DO have, though in imperfect and delayed terms. We can use this, and then put a wide error margin, to see if this gives us a sense.

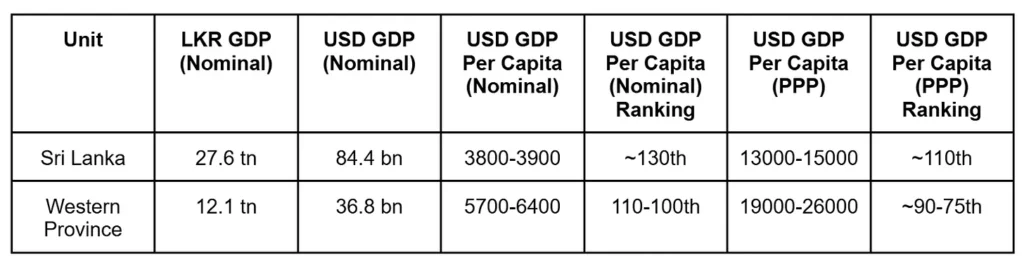

In 2023, the Western Province had nominal GDP of around LKR 12.1 tn. The average USD/LKR exchange rate across 2023 was around 327 LKR/USD, so that puts the USD GDP at around USD 36.8 bn. While we don’t yet have an up-to-date population measure for the Western Province, the most recent estimates put it around 6.1 mn people. If we take a 5% margin around this number to reflect internal migration, we get a population of 5.8-6.4 mn people. That puts GDP per capita at USD 5700-6400 – about 50-60% higher than Sri Lanka’s overall GDP per capita of around USD 3800-3900. On this basis, where Sri Lanka is in the 130th rank for GDP capita for countries, the Western Province jumps to somewhere near the 100th to 110th rank.

But this is all on nominal basis. All of this has to be converted to some sort of inflation and purchasing power adjustment. Here, we don’t have a very good way to do it other than the PPP factor conversion – where you compare the ability to purchase a certain basket of goods in one country vs others. Sri Lanka’s GDP per capita in PPP terms would be around USD 13000-15000. If we apply the same ratio for the Western Province, that takes it to USD 21000-25000. Since in practice, the ratio would probably be different, lets do a 5% margin around this as well to get USD 19000 to 26000 in per capita GDP in PPP terms.

This makes a significant difference. Compared to the nominal per capita rankings of around 130th for Sri Lanka, and 100-110 for Western Province, the PPP per capita for Sri Lanka is itself around the 110th ranking. The newly estimated GDP per capita in PPP for the Western Province goes substantially higher, now ranking somewhere in the 90th to 75th rank!

How rich is the Colombo District?

Another approach we can try, is to take the Colombo district. Here, I’m actually going to start with the Old Colombo district – that is before the partition into Gampaha and Colombo. That is, can we see how rich “Colombo and Gampaha together” is – what I will call Old Colombo?

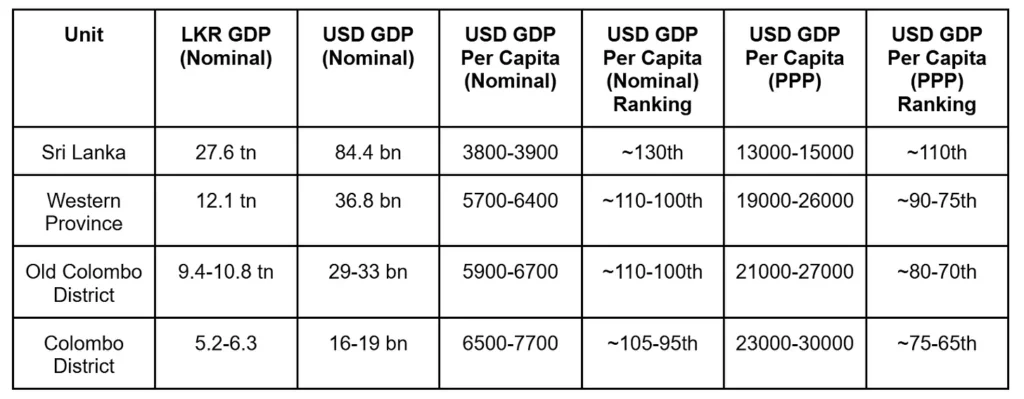

This is much harder since we don’t really have good data or even proxies at this level. The attempt I will use is to take the total “expenditure” by household in the three districts in the Western Province according to 2019 data, and then see what the “proportion” of this is held by the Gampaha and Colombo Districts, and use this to create a proxy GDP for the two.

This tells us that Colombo District has 48% of all expenditure in the Province, Gampaha has 37%, and 15% for Kalutara. Thereby, the combined Old Colombo has around 85% of expenditure. Taking this as 80-90% as a range, this tells us that of the USD 36.8 bn in GDP in the Western Province, USD 29-33 bn is in Old Colombo. With a combined population of around 4.9 mn people, this puts nominal GDP per capita in Old Colombo at USD 5900-6700 . In PPP terms at the same ratio as before, that makes it USD 21000-27000, about 80th to 70th ranked in the world.

But what if we dial down onto Colombo district itself? The same approach gives us a nominal USD GDP of USD 16-19bn, a per capita GDP of USD 6500-7700, and a PPP adjusted per capita GDP of USD 23000-30000, now somewhere near the 75th to 65th ranked country.

Can we get even closer?

Any further and we move pretty heavily into the realm of speculation. Not only are there no strong economic indicators for something like the CMC, nor are there population estimates. Hopefully, after the new census is done we have a little bit more visibility, but other than that the only real option is to use proxies.

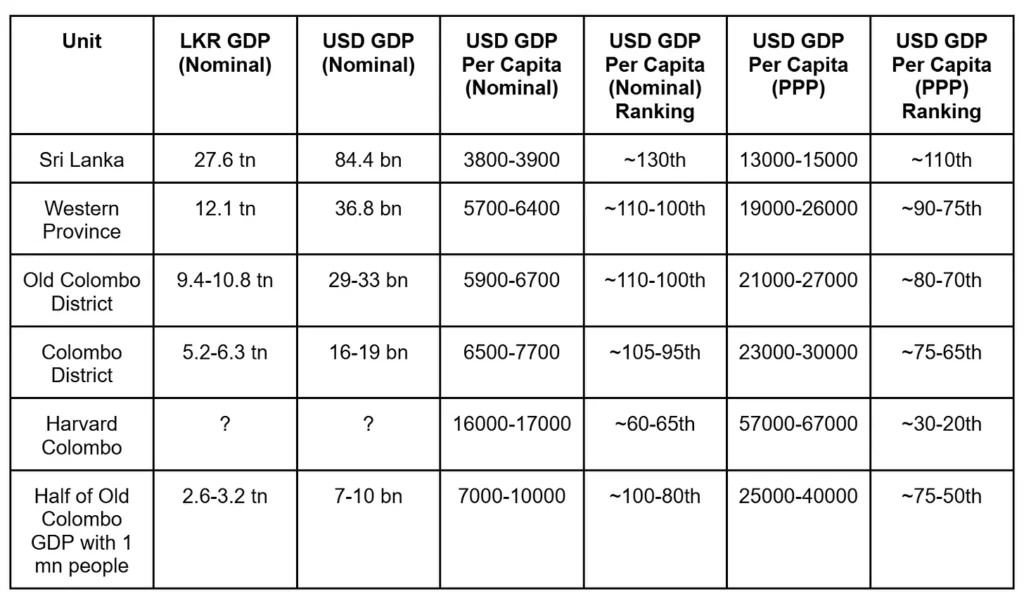

Until we do that, another view we can take here is what the Harvard Growth Lab’s Metroverse has estimated as Colombo’s GDP per capita. Their definition of the city is a bit different to any we’ve taken here, but with a definition that extends the city from Negombo to Beruwala, and a few suburban corridors as well, they give a GDP per capita of somewhere in the USD 16000-17000 range – highest so far that we’ve gotten. It’s not fully clear whether this is PPP terms or not, but the “comparative cities” they have given have nominal per capita in this range. However, the total “GDP” we get from this is arguably too high for Sri Lanka, but population and GDP per capita is “calculated” very differently so they might not be comparable anyway.

If we consider this as a nominal GDP data point, and convert this to PPP terms at the same ratio gives us USD 57000-67000, which puts this definition of Colombo at the 30th to 20th rank. This fits the trend so far of getting richer and richer, the closer we get to the economic heart of what “Colombo” is. If we try to verify this by taking a rough view of “Colombo” as comprising half of Colombo District’s GDP, but across only a million people, we can get somewhere nearby as well – and I would feel that the city generates well more than half of the district’s GDP.

But are these values too high? Particularly given the question of whether the datapoint is nominal or not is not very clear to me, it could very well be. I will leave that question open for now and return to it later with an amenities approach, since it likely relates to the relatively uncommon nature of inequality in Colombo.

All of this is only an exploratory question – numbers alone don’t make a country rich

The biggest question with all of these is does it really ring true? Does Colombo feel like such a rich city? For many people, I suspect the answer is no. There is no real narrative, no real story that Colombo holds that it is truly a rich city. Richer than the rest of the country, sure, but the dominant narrative feels closer to it being the richest city in a poor country.

What these numbers tell us, and other explorations outside of this can as well, is that there is a potential story that Colombo has missed. Missed, in the decades of dreams and despair, missed in crisis after crisis, missed in the grinds of daily life, but missed in the end. Part of it might even be the cyclical nature of South Asian economies that prevent such a narrative from properly taking hold. But in the end, I think we will eventually have to think of and grapple with this narrative as well.

I don’t expect this narrative to immediately take hold. But we can’t forget the fact that since 2018, Sri Lanka, and especially Colombo, has been facing pretty strong contractionary and tightening forces (outside small exceptions). Will this continue? If the overall story of the economy changes significantly enough, Colombo could be looking at a big change in its story as well. This doesn’t have to be a purely positive story of course, but a big change nevertheless. My gut tells me we have to be ready to deal with what a “rich Colombo” means as a story and as a reality.

*The author is a Sri Lankan economist working on macro-advisory, macro-forecasting, and tying sociopolitical factors into understanding economic decisions.

Leave a comment