By Dilrukshi Handunnetti

The administration has failed to ease the economic burden in a tangible way, and the public continues to reel under the skyrocketing cost of living. People pin hopes on a systemic overhaul

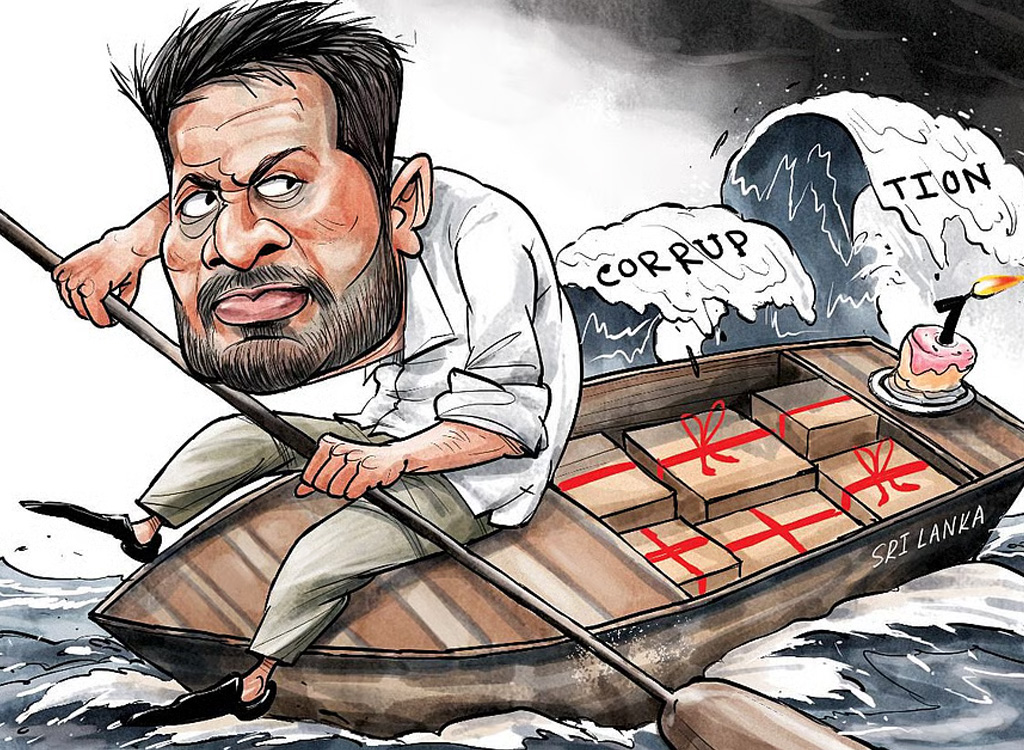

Exactly a year ago, Sri Lankans wrote political history by decisively bringing traditional two-party politics to an end by elevating a party that was not expected to rule. Their radical choice: Anura Kumara Dissanayake, a neo-leftist and leader of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front).

For the JVP, it had not been a cakewalk. For decades, it has struggled to overcome a debilitating three percent vote, which permanently confined them to the opposition ranks. Despite radical appeal, political power had continuously eluded them until Sri Lanka hit an economic nadir in 2022. A simmering governance crisis, combined with an economic crisis, provided a potent formula for seismic political change, and Dissanayake soon emerged as a beacon of hope for a nation tired of corrupt regimes and family rule.

Despite his popularity, Dissanayake’s meteoric rise was the culmination of the 2022 ‘Aragalaya’ protest movement, which forced the then President, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, to resign amid massive public protests. Opinion polls showed Dissanayake as the country’s most trusted politician at the time, as public sentiment strongly opposed the traditional ruling class—amidst allegations of largescale corruption, kleptocracy, nepotism, and a mismanaged financial crisis.

Despite the political upheaval, Sri Lankans also demonstrated political prudence and patience by holding elections and by ensuring a smooth transition of power. When selecting a successor, JVP’s own violent history and the responsibility of two uprisings in the South did not deter voters from electing Dissanayake as their president.

A year on, public expectations remain high, and Dissanayake and his government’s delivery remains a mixed bag. Among the key changes expected was to reset the economic policy. However, Sri Lanka has already signed up for the IMF’s formula for debt restructuring to weather the economic storm. Ultimately, Dissanayake chose economic pragmatism, opting to honour the commitments made while managing domestic priorities—a difficult balancing act.

The government has begun to liquidate identified non-performing public institutions, and the spiralling cost of living is creating public irritation; however, there appears to be a dogged determination within the government to go through the painful process. This brings no praise for Dissanayake, who is criticised for following a Western economic formula, once the topic of acid criticism by the JVP. There is unhappiness about the government’s failure to prosecute the country’s corrupt elite, another lofty election promise.

The NPP, meanwhile, claims to have taken measures to contain the budget deficit and sustain economic growth, while also trying to attract foreign direct investment. Presenting his first budget in February 2025, President Dissanayake informed parliament that four major Port City projects, worth $1.4 billion, are underway. The government also initiated public sector salary reforms to be implemented in phases through 2027, aiming to increase salaries and reduce wage disparities.

Beyond its shores, Sri Lanka is also required to deal with the competing geostrategic interests of both China and India. A member of the Official Creditors’ Committee, India’s bilateral debt to Sri Lanka is approximately $1.74 billion, whereas debt owed to China is primarily for infrastructure projects, totalling $4.9 billion.

To win New Delhi’s favour, Dissanayake had to put in some work. The JVP has a publicly declared anti-India stance and had played a pivotal role in driving the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lankan soil through violent protests in 1987-89. The new administration has been strategically moving forward to strengthen bilateral ties. Symbolic of this shift was the conferring of the highest civilian award, Sri Lanka Mitra Vibhushana, on visiting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi this April.

The administration has failed to ease the economic burden in a tangible way, and the public continues to reel under the skyrocketing cost of living. Recently, the government has scrapped perks from former presidents, a move that has generated mixed reactions, with only some claiming this would not save state funds. Beyond such optics, people pin hopes on a systemic overhaul, particularly in curbing corruption and holding the political elite accountable.

A month ago, former president Ranil Wickremesinghe was arrested by the Criminal Investigations Department for allegedly misusing state funds. It was also the first time a Sri Lankan president had been arrested on any charge. Wickremesinghe, now out on bail, marked the 79th anniversary of the United National Party (UNP) on September 20 in Colombo, where he referred to the current administration as a ‘constitutional dictatorship’. For those fast losing patience with the government, Wickremesinghe’s arrest was the spark they were looking for. For his part, Wickremesinghe has used it to send out a rallying call for all anti-JVP/NPP forces to come together.

Then there are the unmistakable aspirations of the island’s North, where the people overwhelmingly voted in favour of the NPP last November. They broke tradition and placed their faith in a southern politician to deliver justice and bring closure. There are many unresolved issues in the former conflict zones—missing persons, displacement, landlessness, and absence of justice for atrocities committed during years of war. The list is endless, and the people are waiting for the government to start moving. Dissanayake will do well to remember the northern mandate and to honour that fragile faith—one that is not easily given to a southern political leader.

As Dissanayake completes his first year, the nation watches him with cautious optimism. The next four years will prove crucial, not only for the government but also for his presidency, amidst increasing public scrutiny. It is not unusual that the public is restless and is looking for quick fixes. This electoral victory had taken 50 long years to achieve, and it cannot be squandered.

Then there are South Asian political lessons offering a clear warning to all governments, which started with Sri Lanka itself in 2022. South Asia’s quicksand politics are such that there is little patience for unfulfilled promises or ignored aspirations. People seem to not hesitate to drive governments out of office, holding a lesson for everyone—for those in office and those in waiting. The future of a popularly elected government can be cut short by the very people who elected them, and with no notice, should they feel a betrayal of the people’s trust.

*The writer is an award-winning journalist, lawyer, and founder and director of the Colombo-based Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR).

*The article was published in The New Indian Express.

Leave a comment