By Upul Joseph Fernando

Ranil’s UNP won the 2001 general election but fell short of securing the majority required to form a stable government, winning 109 seats. In that election, the UNP polled 45.62% of the vote across Sri Lanka. Ranil inherited a struggling economy.

The economy had hit rock bottom. Chandrika held the presidency, and ministers were sworn in before her. She led the Cabinet. Since she retained the power to dissolve Parliament within a year, even UNP supporters feared the government could collapse at any moment.

Upon assuming power, Ranil signed a ceasefire agreement with Prabhakaran. In response, the JVP, backed by the SLFP, launched two political campaigns—the Protect Motherland Movement and the Patriotic National Movement. They mobilised Buddhist monks, organising protests and demonstrations across the country. Meanwhile, Ranil increased taxes to stimulate the economy. The local government elections were scheduled for March 2002—exactly four months later.

Ranil, as party leader, only participated in Colombo-based meetings during the local government election campaign. He delegated the campaign to Deputy Leader Karu Jayasuriya and S.B. Dissanayake, who had defected to the UNP from the SLFP. A tacit agreement was made that top leaders would stay in the background during the campaign, given the unusual power-sharing dynamic: the President was from one party and the Prime Minister from another.

Despite this, the UNP won all but four or five local government institutions, securing nearly 60% of the vote. In the 1982 referendum, Attanagalla—birthplace of the Bandaranaikes—was reportedly lost due to mob violence. But for the first time in Sri Lanka’s political history, the UNP won Attanagalla peacefully. It was, at the time, the President’s constituency. Mahinda also lost all local government bodies in his Hambantota district. The UNP’s triumph came despite fierce resistance backed by presidential authority, winning 217 out of 222 local bodies.

The 2002 local government election mirrors the situation faced by the National People’s Power (NPP) in today’s elections.

The JVP contested this election while holding a two-thirds majority and the executive presidency. The opposition had been marginalised to the point that senior SLPP and opposition figures, including former ministers, opted not to run.

The JVP had won 61.56% in the general election—a historic result under the proportional representation system, as no party had previously secured a two-thirds majority this way. The Rajapaksas had earlier cobbled together a two-thirds majority by absorbing opposition MPs.

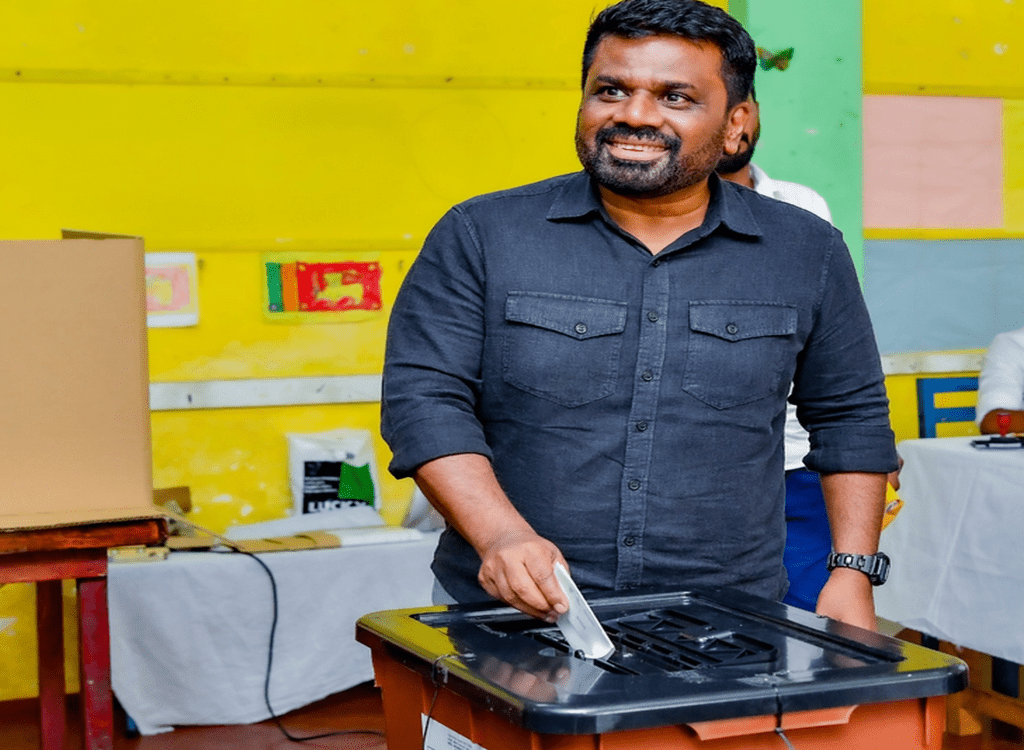

In this local government election, opposition parties avoided open-air rallies, fearing poor attendance. Instead, they held indoor meetings. Only the JVP held public rallies, all of which President Anura personally attended. Typically, Sri Lankan presidents only attend a few local campaign events, but Anura treated this as both a presidential and general election—his election.

Expectations were sky-high: many believed the JVP would win over 60% of the vote, even in the North-East. JVP Secretary Tilvin predicted a 70% share, while Prime Minister Harini claimed they would surpass their results in both the general and presidential elections.

The JVP framed the 2024 general election as a “shramadana” (voluntary effort) to uproot 76 years of corrupt politicians—likened to weeds. They labelled the local government elections as the symbolic burial of a 76-year curse.

The results, however, followed a familiar pattern. In Sri Lanka’s democratic history, local government elections held within six months of a presidential or general election typically favour the winning party. These elections consolidate political momentum, allowing the ruling party to exceed its previous vote counts and percentages. Such outcomes reaffirm the public mandate already given.

Consider Mahinda’s 2005 victory: he won the presidency with 50.29% on 17 November 2005. Four months later, in local government elections, he improved his share to over 55%, winning 225 out of 266 local bodies—around 83%. Notably, Mahinda achieved this without the JVP, which contested separately, and despite not leading the SLFP or having a parliamentary majority.

Similarly, Ranasinghe Premadasa won 50.43% in the 1988 presidential election. Three years later, in local elections, he increased his vote share and won across all southern districts, including Anuradhapura, which he had previously lost.

In 2010, Mahinda won the presidency with 57.88%, and a year later, in 2011, he maintained 56.45% in local elections—still a strong showing despite the typical dip in government popularity after a year.

In 2004, the general election in April gave Chandrika’s United People’s Freedom Alliance 46.60%. By July, in the local government elections, they had surged to 57.68%.

So how did the JVP, which swept the presidential and general elections with 61.56%, drop to 43.26% within six months?

How did they lose over 2.4 million votes?

This outcome defies belief. Anura and his team appeared to politicise the sacred Tooth Relic exposition—a revered symbol for Sinhala Buddhists—for electoral gain. Was his symbolic act at Galle Face meant to project the absence of credible opposition? Was his trip to Vietnam, mid-campaign, intended to position himself as a global Sinhala Buddhist leader?

The unexpected victor of this election is Sajith Premadasa. Many expected this minor election to mark the end of his political relevance. On May Day in Talawakele, just before the vote, all major parties—NPP, UNP, and SLPP—criticised him for leaving the rally early. But the electorate demonstrated that Sajith remains the only viable alternative and a potential leader ready to assume power.

Normally, opposition parties lose ground in elections held six months after a national vote. That’s the usual political tide. But this time, all opposition parties—including Sajith’s Samagi Jana Balawegaya—gained ground, bucking the trend.

So what happened to Anura?

Before the local elections, Anura styled himself after Ranil Wickremesinghe—holding discussions with business leaders and cultivating an image as an IMF-aligned reformist. The JVP framed him as an IMF hero, highlighting World Bank loans under his administration.

But after the local elections were announced, Anura shifted gears. He began emulating Mahinda Rajapaksa—organising the Dalada Exhibition and attending Vesak celebrations in Vietnam, attempting to position himself as a Sinhala Buddhist figure.

Yet the people elected Anura to be himself. Ironically, the JVP embraced him as a cleaned-up version of Wijeweera—sanitised, but still symbolic—revealing that Anura ultimately failed to grasp his own political identity.

*The article was originally published on Sri Lanka Guardian.

Leave a comment