By Dr Mahim Mendis

“A university ceases to be a university the moment it loses the freedom to govern itself.” – Professor Clark Kerr, first chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley

The Sri Lankan university system has, until now, jealously safeguarded the principle of university autonomy—a principle without which a university ceases to be a university in the true sense. The intellectual and administrative traditions governing Sri Lanka’s public universities were shaped at their inception by Sir Ivor Jennings, the founding Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ceylon, drawing deeply from the time-tested conventions of British universities and the broader Commonwealth academic tradition. These conventions were not accidental customs; they were carefully evolved practices designed to protect intellectual freedom, collegial governance, and meritocratic leadership.

For decades, these traditions stood above individuals and regimes, whether academic or political. They survived changes of government, ideological shifts, and national crises because they were grounded in the understanding that universities must remain self-governing communities of scholars, not instruments of state power.

When Conventions Are Legislated, Universities Begin to Collapse

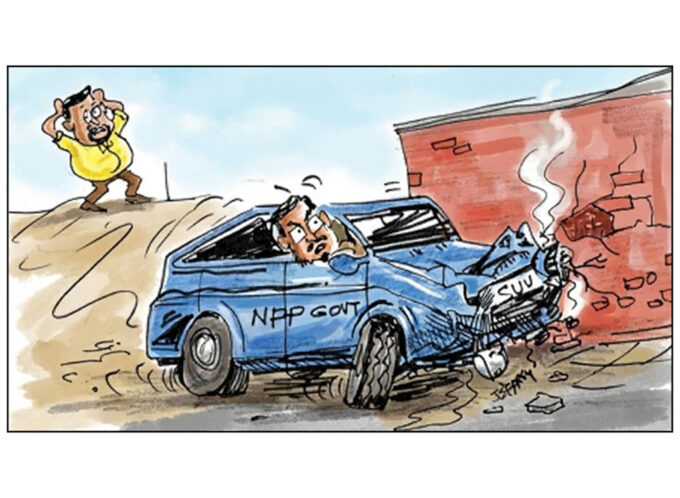

The moment these conventions are politically redefined through coercive legislation, Sri Lanka risks the accelerated destruction of its national university system. At the heart of the present crisis is not reform, but authoritarian centralisation masquerading as administrative efficiency.

Universities cannot be governed in the same manner as line ministries or state corporations. Their legitimacy flows from intellectual authority, peer respect, and academic integrity. When the state seeks to legislate internal academic norms, it substitutes political logic for scholarly reason—a substitution that invariably ends in decline.

Academic Leadership Is Earned, Not Imposed

Academics—the country’s intelligentsia—do not need to be instructed by politicians on how universities should be governed. They understand, from lived professional experience, that academic leadership is earned, not imposed.

A university department functions effectively only when led by a colleague who commands intellectual respect and professional trust. The culture of academic work depends on collegiality, mutual respect, and peer legitimacy. Authority imposed from above—whether through political appointment or administrative fiat—inevitably weakens morale, productivity, and intellectual honesty.

Why Deans Matter: The Faculty as an Intellectual Community

The office of Dean is not merely ceremonial; it is the chief academic and administrative leadership position of an entire faculty. Faculties are complex intellectual ecosystems composed of multiple departments and disciplines.

Leadership over such bodies requires not only academic distinction, but proven administrative competence and an earned reputation that transcends disciplinary silos. Undermining this principle reduces faculties to bureaucratic units rather than communities of scholarship.

A Circular Without Authority: Executive Overreach at the UGC

Against this background, recent actions attributed to the University Grants Commission are deeply troubling. The circular addressed to Vice-Chancellors dated 18 December 2025, directing that elections of Deans and appointments of Heads of Departments be halted pending new regulations, represents a serious procedural and ethical rupture.

This directive lacks a clear legal basis under the law currently in force. Vice-Chancellors remain bound by existing legislation, not by anticipated amendments. Acting otherwise undermines the rule of law and erodes institutional credibility.

Centralisation as a Prelude to Authoritarianism

The proposed amendment seeks to dismantle long-standing democratic academic practices by transferring authority over appointments to Vice-Chancellors or university councils. This centralisation of power is especially dangerous in a politically charged environment.

Granting unilateral appointment powers opens the door to patronage, ideological conformity, and institutional fear. Universities thrive on dissent and debate; authoritarian structures suffocate both.1

The Most Dangerous Provisions: Why the Proposed Amendment Is Fundamentally Autocratic

At the core of the proposed amendment lie provisions that represent a direct assault on democratic academic governance. Chief among them is the removal of the long-established system through which Deans and Heads of Departments are elected or selected through participatory academic processes. In its place, the amendment seeks to concentrate decision-making authority either in the hands of the Vice-Chancellor or within university councils that are increasingly vulnerable to political influence.

This shift is not a neutral administrative adjustment. It marks a structural transfer of power away from the academic community toward individuals or bodies whose legitimacy does not arise from scholarly peer recognition. Granting unilateral authority to appoint Heads of Departments effectively converts academic leadership into an act of executive discretion. Such power, once normalised, creates conditions ripe for favouritism, ideological filtering, and the silencing of dissenting academic voices.

Equally troubling is the proposed empowerment of university councils without first ensuring that these bodies are genuinely representative of academic professional autonomy. Councils that are inadequately insulated from political pressure cannot be entrusted with decisions that fundamentally shape intellectual life within universities. Instead of acting as buffers between the state and the academy, they risk becoming conduits for external interference.

Taken together, these provisions introduce a governance model that is top-down, centralised, and coercive in character—a sharp departure from the collegial traditions that have defined Sri Lankan universities for generations. This is the very definition of autocracy within an academic setting: authority imposed rather than earned, compliance valued over competence, and loyalty rewarded over intellectual integrity.

The public must understand that once such provisions are enacted, their consequences will not be easily reversible. Universities will no longer function as communities of independent scholars, but as administratively controlled institutions where academic judgment is subordinated to executive will. This is not reform. It is the institutionalisation of fear and conformity, and it strikes at the heart of Sri Lanka’s democratic and intellectual future.

Comparative Constitutional Perspectives: How Democratic Systems Protect University Autonomy

A comparative constitutional analysis clearly demonstrates that the proposed amendment places Sri Lanka outside accepted democratic and Commonwealth norms governing higher education.

In mature democracies, university autonomy is not treated as a discretionary administrative privilege, but as a constitutional or quasi-constitutional principle essential to democratic governance.

In the United Kingdom, from which Sri Lanka originally inherited its university traditions, academic self-governance is protected through entrenched conventions rather than ministerial control. British universities operate under a system of collegial governance where academic leadership positions—such as heads of departments and deans—are filled through internal academic processes grounded in peer legitimacy. Even in cases of structural reform, the state has consistently avoided direct intervention in academic appointments, recognising that intellectual independence cannot coexist with executive control.

In India, whose constitutional framework Sri Lanka has often drawn upon, the Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed that universities occupy a special constitutional space. Indian constitutional jurisprudence recognises that academic freedom and institutional autonomy are intrinsic to the fundamental right to freedom of expression and the advancement of knowledge. Judicial interventions have consistently warned against excessive state interference in university governance, particularly where such interference threatens academic independence or merit-based decision-making.

In South Africa, the post-apartheid constitutional order explicitly affirms academic freedom and institutional autonomy as essential to a democratic society emerging from authoritarian rule. University governance reforms there have prioritised participatory decision-making and strong internal academic representation, precisely to prevent the re-emergence of political domination over knowledge institutions.

By contrast, in states that have experienced democratic backsliding, such as Hungary and Turkey, the erosion of university autonomy has followed a recognisable pattern:

centralisation of appointment powers, politicisation of governing councils, weakening of peer-based academic authority, and the use of “reform” rhetoric to justify authoritarian consolidation. In each case, universities were among the first institutions to be structurally subdued, leading to international isolation, academic decline, and long-term damage to democratic culture.

Sri Lanka’s proposed amendment regrettably mirrors these illiberal trajectories rather than aligning with Commonwealth democratic practice.

From the standpoint of international norms, instruments promoted by UNESCO consistently affirm that academic freedom and institutional autonomy are inseparable from democratic governance, social progress, and sustainable development. While these principles may not always be explicitly codified in constitutions, they function as normative constraints on state power in democratic societies.

Against this comparative background, it is evident that the proposed amendment represents a constitutional regression, even if framed as a statutory reform. By centralising authority, weakening collegial governance, and enabling executive dominance over academic appointments, it violates the spirit of constitutionalism that underpins democratic higher education systems worldwide.

A Troubling Political Context

The current JVP-inspired Malimawa regime appears determined to implement politically motivated schemes with alarming haste. Such urgency often signals an intolerance of deliberation—a hallmark of authoritarian governance.

When governments rush to control universities, they reveal a deeper anxiety: independent thought is perceived as a threat rather than a public good.

Universities and Democracy: An Indivisible Relationship

Warnings from national political leaders, including the Leader of the Opposition, that these actions represent a drift toward authoritarian decision-making should be taken seriously. This is not a partisan matter.

Globally, the erosion of university autonomy has consistently preceded democratic backsliding. From Eastern Europe to South Asia, universities are often the first institutions targeted by illiberal regimes seeking ideological dominance.

Reform Must Strengthen, Not Weaken, Academic Self-Governance

Sri Lanka does not require coercive legislative control over universities. What it needs is the strengthening of genuinely representative university councils, insulation from political interference, and respect for internal academic decision-making.

True reform empowers scholars; it does not silence them.

A Call to Sri Lanka’s Intelligentsia—and to the World

This moment demands vigilance from Sri Lanka’s intelligentsia and solidarity from the international academic community. The future of higher education in Sri Lanka cannot be sacrificed for political expediency.

Universities exist to question power, not to submit to it. Any amendment that undermines this foundational principle is not reform—it is regression. The time to act is now, before the damage becomes irreversible.

Leave a comment