By Ruisiripala Tennakoon

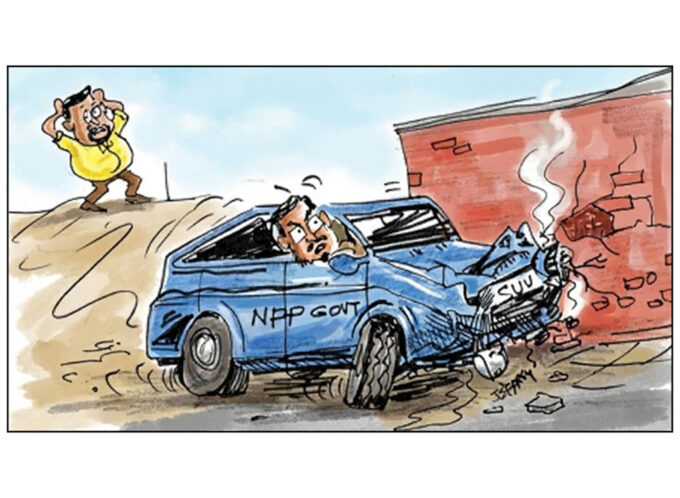

Sri Lanka’s recent policy shift on vehicle imports, while politically popular and superficially comforting to consumers, raises deeper economic concerns that cannot be ignored. What appears today as a controlled easing of restrictions may, if left unchecked, evolve into a policy-induced financial vulnerability—one that bears uncomfortable similarities to the chain of events that led to the 2007/2008 global financial crisis in the United States.

This reality deserves careful attention in Sri Lanka’s current context, where several thousands of vehicles are already awaiting shipment against letters of credit that have been opened, while hundreds more remain idling with vehicle dealers pending disposal due to weak demand and sharp market fluctuations driven by rapidly changing exchange rates. These commitments, though not yet fully reflected in official statistics, represent a latent and imminent draw on foreign exchange. Once released into the system, they will simultaneously strain reserves, deepen household and institutional credit exposure, and accelerate asset value corrections—well before policymakers have adequate room to recalibrate.

The American crisis did not begin with the collapse of banks. It began quietly—with well-intentioned but poorly regulated policies encouraging asset acquisition through easy credit. Housing, once considered a stable store of value, became an instrument of speculative excess. Household debt expanded faster than income, asset prices inflated beyond fundamentals, and financial institutions mistook volume for stability.

Sri Lanka’s vehicle import liberalization risks following a comparable trajectory, albeit through a different asset class.

Vehicles in Sri Lanka are not mere consumer goods. They function as quasi-assets—often purchased through long-term leasing, used as collateral, and priced heavily in foreign currency terms. When imports were restricted, vehicle values remained artificially elevated, masking the true exposure of banks and leasing companies. The sudden reopening of imports, without a calibrated credit and exchange-rate framework, threatens to reverse this illusion abruptly.

A surge in imports inevitably leads to an immediate outflow of foreign exchange. At a time when Sri Lanka is still rebuilding external buffers with considerable effort, this additional pressure on reserves introduces avoidable stress. More critically, aggressive competition among financiers to capture vehicle buyers may lead to relaxed credit standards, longer repayment tenures, and higher household leverage.

This is where the parallel becomes concerning.

In the US, the subprime crisis was not caused merely by falling house prices, but by the interaction between asset price declines and highly leveraged balance sheets. When prices corrected, borrowers found themselves owing more than the value of their homes. Defaults followed, securitised instruments failed, and a liquidity crisis rapidly became systemic.

In Sri Lanka, a sharp increase in vehicle supply could lead to rapid depreciation in resale values. If borrowers are locked into high-value leasing contracts based on inflated prices, the correction will weaken both household balance sheets and the asset quality of financial institutions. Unlike housing, vehicles depreciate faster, making the risk even more immediate.

This is not to suggest that Sri Lanka is heading toward a global-scale financial collapse. Our financial system today is more tightly regulated, and recent painful experiences have instilled a degree of institutional caution. However, history teaches us that crises rarely announce themselves dramatically. They emerge from policy blind spots, especially when short-term relief is prioritised over long-term stability.

The danger lies not in vehicle imports per se, but in amateurish sequencing—opening imports without:

- clear credit controls,

- differentiated taxation linked to FX impact,

- stress testing of leasing portfolios,

- and coordination between fiscal, monetary, and external sector policy.

A responsible policy approach would recognise that consumption-led recoveries funded by foreign exchange and domestic credit are inherently fragile. True economic revival must be anchored in export growth, productivity gains, and income expansion—not asset-heavy consumption financed by debt.

Sri Lanka has already paid dearly for ignoring early warning signs in the past. We should not require another painful lesson to relearn what economic history has repeatedly shown: when asset bubbles meet easy credit and weak oversight, the outcome is never benign.

This moment should serve as a pause for reflection—not celebration.

Leave a comment