By Vox Civis

Karma has a funny way of catching up. The very people who laughed at and mocked former President Ranil Wickremesinghe when he declared that Sri Lanka would become a developed country by 2048 are now making a similar prediction, pushing the date back even further. Under the direction of the current National People’s Power (NPP) administration, Sri Lanka, we are told, will reach that milestone no earlier than 2060. That’s a staggering thirty-five years from now.

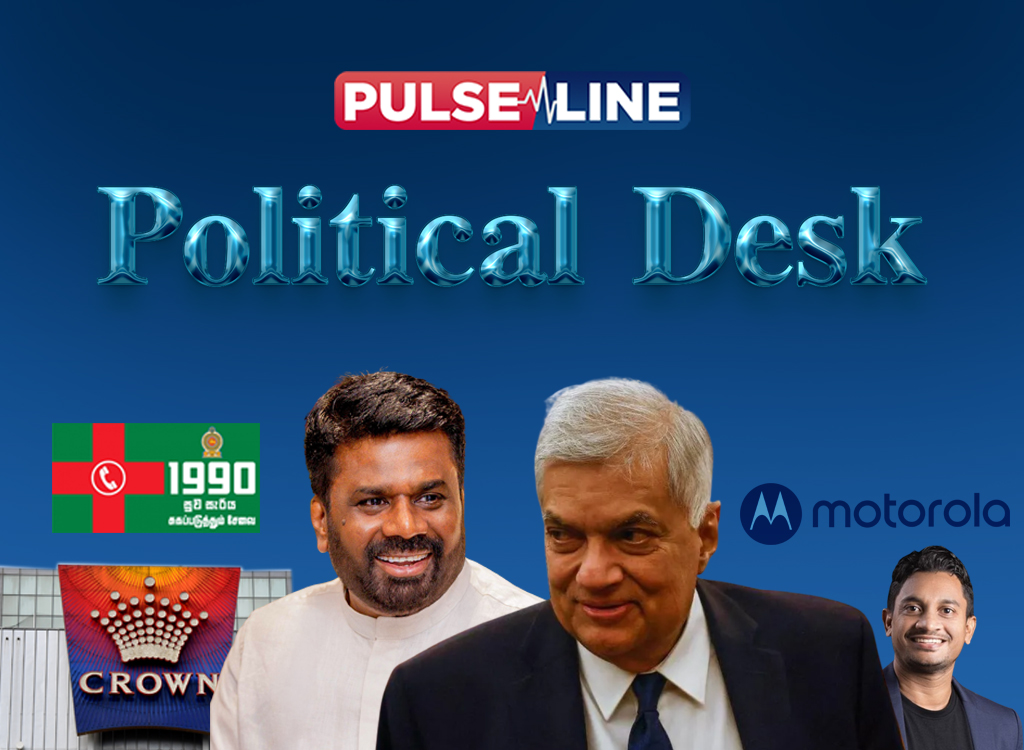

The pronouncement came from an influential Deputy Minister – currently under fire for proposing sweeping changes to the popular free ambulance service, Suwaseriya – while speaking at a public forum in Colombo last week. The unmistakable irony is that those who once dismissed Wickremesinghe’s long-term vision at times as fanciful and other times as indicative of inability to deliver sooner, are now embracing an even more distant horizon, albeit under their own banner.

In just over a year in office, the NPP has managed to reverse nearly all of its pre-election promises and hitch its wagon to the very policies of the Wickremesinghe administration it once condemned. The latest such reversal came when the President himself began openly advocating for the privatization of government-owned assets, needless to say a dramatic departure from the fiery anti-privatization rhetoric that powered the NPP’s rise.

Mea culpa

Speaking at the Ratnapura District Secretariat during a District Coordinating Committee meeting last week, the President advocated converting local government-owned supermarkets and commercial ventures to private management, citing as examples the neglected supermarkets in Nugegoda, Borella, and Rajagiriya. The President declared that the state could no longer bear the burden of running commercial enterprises. In other words, mea culpa.

While this is the policy direction adopted by almost all parties that have governed this nation since the introduction of the open economy in 1977, it is the left-wing parties in general and the JVP in particular that vehemently opposed privatisation. Therefore, the President’s complete volte-face from the NPP’s stated pre-election policy, raises legitimate questions about the validity of its mandate. People voted for what the NPP promised, not for what Wickremesinghe envisioned. If the government is now implementing, almost word-for-word, the economic model of the former regime, then one is entitled to ask as to under which mandate it is governing?

For the better part of five decades, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), the ideological heart of the NPP, was unrelenting in its opposition to privatization. It took to the streets, mobilized tens of thousands, and often brought cities to a standstill to oppose what it branded as “traitorous policies.” From protests against Free Trade Agreements to strikes opposing public–private partnerships, the JVP’s resistance has been nothing short of legendary.

A movement in reverse

But it appears that one year in government was all it took for reality to sink in and for rhetoric to give way to pragmatism. For President Anura Kumara Dissanayake himself to now declare that privatization is the way forward marks the height of irony. The real tragedy, however, lies in the incalculable cost of lost time and lost opportunities. Had Sri Lanka not squandered decades fighting ideological battles against market reforms, it might already be well on the road to becoming a developed country, without having to wait for 2048 or 2060.

Among the most notable missed opportunities are the big boys like Motorola bypassing the Free Trade Zones, USD 1.5 billion investment proposed by James Packer’s Crown Casino project in 2012, the Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement (ETCA), several bilateral Free Trade Agreements with Singapore, India, Malaysia, and Thailand, and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact from the United States, which included a USD 500 million outright grant. All were derailed or delayed due to political grandstanding and ideological blindness.

It was Wickremesinghe who consistently argued that idle state infrastructure from tourist bungalows to post offices and market complexes should be handed over to the private sector. He warned that state-run ventures had decayed into financial burdens.

Déjà Vu in Ratnapura

Speaking at the Ratnapura meeting, President Dissanayake echoed these identical sentiments, effectively turning on its head a decades-long anti-privatization stance and reneging on a major pre-election pledge. At the meeting, the President is also supposed to have instructed officials to ensure that development project allocations are fully utilized within the fiscal year, warning that unspent funds being returned to the Treasury would stall progress. “When funds are repeatedly reallocated to the same projects, new development cannot begin,” he cautioned; words that could easily have come from Wickremesinghe himself.

The symbolism is nothing short of striking. Ratnapura being the heartland of the JVP’s early grassroots activism – its leader now stands as the pragmatic technocrat, making the same arguments long derided as capitalist heresy. In the streets and across social media, the President’s remarks have reignited an old ideological debate between those who see privatization as efficiency and those who see it as betrayal. Dissanayake now echoes Wickremesinghe’s assertion that “the government has no business running hotels or swimming pools” and that business should be left to private enterprise while the state focuses on regulation, taxation, and reinvestment.

The same hymn sheet

Up until just a year ago, the NPP accused Wickremesinghe of being a ‘traitor to the nation,’ for selling state property to corporate cronies under the guise of reform. Now, the tables have turned. It is Dissanayake who is advocating the very same reforms and yet the opposition has been strangely hesitant to pin that same label on him.

The JVP’s long-held mantra has been that what was presented as ‘reform’ was, in fact, the liquidation of national wealth. Its leaders argued passionately that if private companies could profit from state assets, so could the government. Today, those same leaders have been forced to confront their own contradictions. It appears that both the President and the NPP he leads are learning the hard way that it’s easy to criticize in opposition, but difficult to practice what you preached once in power.

The hybrid movement

Adding another twist to this unfolding drama is the ideological complexity within the NPP itself. The JVP, by most accounts, retains around 300,000 core members – a disciplined but doctrinaire cadre. The NPP, however, is something else entirely. It is a hybrid movement that attracted 6.8 million votes, the majority of whom do not subscribe to traditional leftist ideology. That contradiction is now coming home to roost.

Faced with a rapidly eroding public expectations, the President appears compelled to take Wickremesinghe’s capitalist route. With a year already gone and little tangible progress to show, he has perhaps realized that slogans and symbolism will not deliver what was promised. The regime seems to have sensed the general sentiment that the country needs to move forward, and fast and that there is no longer any point signaling left and turning right.

The JVP which always denounced liberal economic principles as tools of exploitation, is now swallowing its own bitter medicine. Who would have thought that barely a year after a rousing electoral victory based on a leftist agenda, the NPP would be embracing the founding philosophy of both the UNP and the SJB: liberal economics balanced with social welfare?

Invisible hand of history

It is to the credit of the UNP that every Sri Lankan government since independence – regardless of political colour – has, in practice, followed the economic framework it introduced. From J.R. Jayewardene’s open economy in 1977 to the present day, even self-proclaimed socialist governments have found no viable alternative. No one, not even the most ardent populist, has come up with a different model that works. The NPP’s recent embrace of state–private partnerships is only the latest validation of this reality.

The stark irony is that the NPP which came to power by demonizing Wickremesinghe’s economic model, is now implementing that very same model – line by line. At its core, it is no longer a clash between political parties but between idealism and necessity. The NPP government, weighed down by the realities of governance, has learned that slogans cannot balance budgets and populism cannot substitute for policy.

The same voices that routinely accused right wing parties and notably the UNP of ‘selling the nation’ have been compelled to defend public–private ventures as ‘pragmatic modernization.’ In doing so, they run the risk of being labelled a movement that signals left but turns right.

Idealism and necessity

This profound departure from years of ideological orthodoxy is bound to cause deep internal fissures. Already, signs of unease are visible within the NPP’s ranks. Some members whisper privately that the “NPP tail is wagging the JVP dog,” while others question how a movement born from Marxist ideals can so quickly undermine itself by championing privatization and corporate partnerships. People are asking whether the promised system change is quietly turning into system recycle.

Meanwhile, in Ratnapura – far from the ideological battles in Colombo – people’s concerns remain grounded and practical. Many locals question why the government is focusing on selling state assets under the guise of tourism development when fundamental industry problems remain unaddressed. They point out that what the region actually needs is a proper mechanism for gem trading, being the country’s gem producing hub.

Measures should be taken to divert foreign tourists to the Ratnapura gem market and not to old state buildings turned in to hotels as the private sector has already fulfilled that requirement. These neglected buildings could instead be turned into complementary services for the gem trade such as modern laboratories to authenticate gems, as the region still does not have a single proper certification facility. For the people of Ratnapura, a high-end hotel is far less urgent than a functioning, trustworthy gem industry that can attract both investors and tourists; a reminder that development is meaningful only when it meets the real needs of the people.

Full Circle

In the end, Ranil Wickremesinghe’s call for privatization and the NPP’s reluctant acceptance of it exposes the deeper truth that Sri Lanka’s political divide is more rhetorical than real. From the JVP’s fiery Marxism of the 1970s to the NPP’s supposed technocratic pragmatism of today, the ideological pendulum has swung full circle. The very economic model that has historically been denounced by the JVP as the “root of all inequality” has now become its only viable roadmap for progress.

It is poetic justice or perhaps divine irony, that those who mocked Wickremesinghe are now guided by his playbook. Those who made it their life’s mission to dismantle his system now find themselves trying to survive by piecing it back together. Karma, as they say, has a remarkable sense of timing.

Leave a comment