By Kusum Wijetilleke

It is necessary to submit that the Minister of Education, Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, is perhaps one of the most qualified elected officials to hold the portfolio in recent decades. The no-confidence motion brought by the Parliamentary opposition against the Minister of Education is symbolic, or at least, it is necessary to re-frame it as such. The point is beyond typographical errors in examination papers or administrative lapses, exam papers being leaked, errors in questions or misprinted papers. The recent controversy surrounding a weblink to an adult website being included in a Grade 6 English Exam module is another symptom of a deeper problem and it is tied to the NPP Government, its Prime Minister and the wider policy agenda of the administration.

The fundamental policy U-turn on education investment, was one of the NPP’s central promises during the campaign, led by the career educator and activist, Prime Minister Dr. Harini Amarasuriya. Just six months ago there were past images circulating on social media of the Prime Minister campaigning for the very specific 6% of GDP budgetary allocation to the education sector. This “6%” is very much an aspirational goal since no low-middle income country (LMIC) has succeeded in maintaining such high levels of education spending, but directionally, it is precisely what the country needs. A generational overhaul of the country’s education system, at all levels, is a fundamental non-negotiable to build a Sri Lanka that can meet the challenges of the future and depart from this trajectory of economic stagnation and LMIC mediocrity.

This is not a critique of Dr. Amarasuriya; there is little doubt that she believes in the principle of a free, accessible, well-funded education system, with well-paid teachers, high-quality, well-equipped facilities and a syllabus that is based on global standards while maintaining Sri Lanka-relevant content. However, this administration came to power pledging a decisive break from decades of underinvestment in public education. Yet the numbers tell a starkly different story. Education spending has remained around 0.9% of GDP in the first year as per Budget 2025, rising only marginally to approximately 1.1-1.2% of GDP as per budget 2026; this does not point to a government that has made its education sector a priority.

It is less a case of reforms being delayed and more a case of reforms having been quietly abandoned. The Prime Minister should by now be fully aware of this reality, particularly as the minister responsible for a major institution that is central to Sri Lanka’s next phase of development.

Line ministers are acutely conscious that their ministries depend on public funding, yet education in Sri Lanka has been systematically under-invested in for decades. The country records one of the lowest levels of education spending among its peer group and suffered some of the largest education losses globally during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the same time, Sri Lanka aspires to position itself in global markets for high-value services, advanced financial services, and technology-driven sectors. The obvious question is: where will the talent for these sectors come from? Sri Lanka already faces acute shortages across the skills spectrum, from electricians, plumbers, and construction workers to engineers and technical professionals.

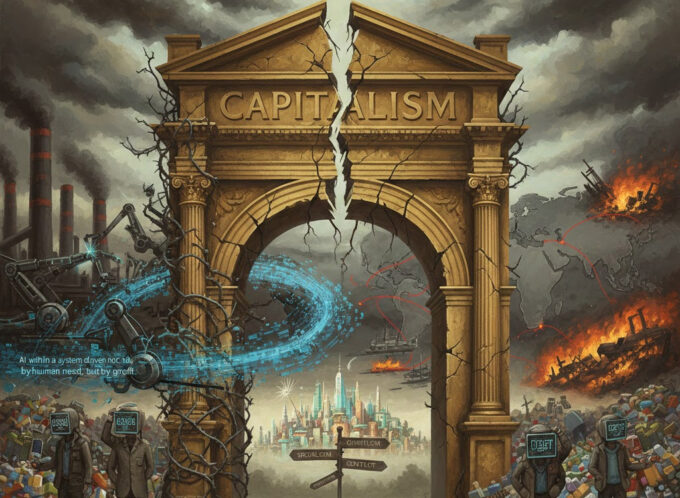

We are also entering an intensely competitive technological transition. Unless Sri Lanka’s education and skills systems are urgently modernised, the country’s labour force will become increasingly uncompetitive or redundant, in the global marketplace, undermining both growth ambitions and social mobility.

The NPP Government’s about-turn, having been voted into power on a popular wave of disenchantment, seems content with the incrementalism of its predecessor, led by Ranil Wickremesinghe, whose policy agenda and trajectory remain. The NPP’s embrace of Wickremesinghe’s austerity program could well be its own downfall; the education ministry and the current controversy are just symptoms of this wider issue. In Democratic societies, a political party that espouses certain principles during a campaign is bound by democratic ethics to abide by the promises made to the public to earn their vote.

History offers sobering lessons about what happens when governments secure power on broad, moral claims and then quietly retreat from their most central commitments.

In Greece, the left-wing Syriza rode to office in 2015 on an explicit anti-austerity mandate, promising to reverse cuts to social spending and public services. Within months, under external and internal pressure, the government implemented many of the same fiscal restraints it had condemned. The political damage was immediate and lasting: voter trust collapsed, party cohesion fractured, and cynicism toward democratic promises deepened.

In the United Kingdom, the Conservative Party returned to power in 2010 claiming it would protect frontline public services while pursuing fiscal responsibility. In practice, deep cuts to education, local government, and youth services followed. The long-term consequences: declining school infrastructure, regional inequality, and social fragmentation, continue to shape British politics more than a decade later. These examples illustrate a simple political truth: when governments retreat from their defining promises, legitimacy erodes far faster than administrative credibility. Just take a look at the UK Conservative Party today.

Mistakes in examination processes are often symptoms of understaffed departments, outdated systems, and institutional stress. Those conditions are produced not by individual negligence, but by chronic underfunding and the absence of serious reform. If education was truly the government’s priority, the response would not have been defensive explanations or bureaucratic blame-shifting. It would have been a visible, measurable commitment to funding, reflected clearly in the budget, in staffing levels, in infrastructure investment, and in long-term planning. Instead, what we have seen is a quiet normalisation of the status quo.

A no-confidence motion in this context is not punitive; it is principled. It asserts that governments are accountable not just for errors, but for broken mandates. When an administration campaigns on transformation and then governs through continuity, voters are entitled to ask whether consent still exists.

(The writer is a political commentator, media presenter, and foreign affairs analyst. He serves as Advisor on Political Economy to the Leader of the Opposition of Sri Lanka and is a member of the Working Committee of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB). A former banker, he spent 11 years in the industry in Colombo and Dubai, including nine years in corporate finance, working with some of Sri Lanka’s largest corporates on project finance, trade facilities, and working capital. He holds a Master’s in International Relations from the University of Colombo and a Bachelor’s in Accounting and Finance from the University of Kent (UK). The writer can be contacted via [email protected] and Twitter: @kusumw)

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of this publication.

Leave a comment