Medical professionals have voiced serious reservations over a new directive issued by the Ministry of Health governing the procurement of drugs and surgical items by state-run hospitals from third-party sources.

While the circular is intended to streamline medical supply shortages and safeguard patient care, clinicians warn that it introduces significant operational, ethical, and logistical complexities.

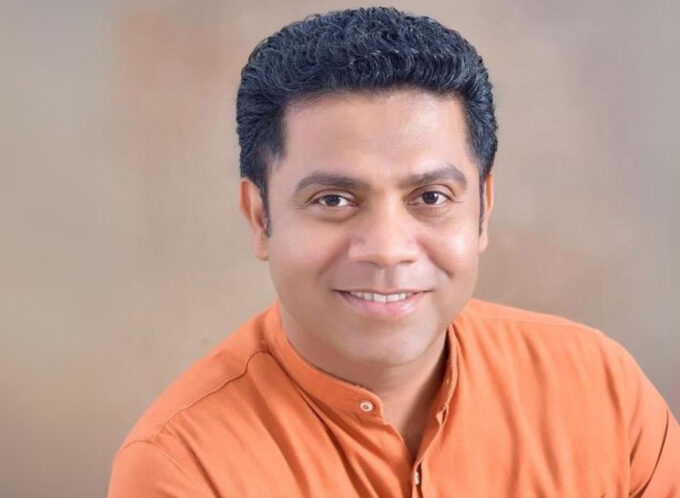

The circular was released in the wake of mounting pressure from specialist doctors following explosive allegations against Dr. Maheshi Wijeratne, a senior neurosurgeon at the Sri Jayewardenepura General Hospital who is accused of selling surgical equipment at inflated prices through a private entity.

The Health Ministry’s guidelines now permit patients to purchase unavailable medical items—including high-cost consumables such as surgical staplers and meshes—from outside sources, provided they are unavailable at the hospital.

However, medical specialists argue that the circular, while well-intentioned, leaves critical questions unanswered.

Vagueness undermines implementation

Key terms such as “best interest” and “highest ethical standards” are highlighted as particularly problematic as they are open to subjective interpretation and risk inconsistent implementation across hospitals. Doctors are calling for more precise definitions to guide ethical decisions and maintain professional accountability.

In addition, the circular mandates that each clinical unit must receive written, daily updates on unavailable drugs and supplies.

Without these updates, consultants say they cannot fulfil the requirement to confirm unavailability before requesting patients to procure items externally.

“We’re being asked to certify that an item is not in stock, but without formal notice from the hospital pharmacy, how can we do so responsibly?” a senior physician at a leading teaching hospital queried.

Strain on staff and resources

Medical specialists point to the burden of logistics. With many wards experiencing routine shortages of basic items—from antibiotics to enemas—the requirement to issue written declarations for every purchase could prove unmanageable.

Concerns have also been raised over the availability of declaration forms and the consistent presence of authorised officers and pharmacists to process approvals, especially during nights and weekends.

Drug quality and safety under scrutiny

The absence of clarity on whether third-party drugs must meet National Medicines Regulatory Authority (NMRA) certification standards has also triggered alarm.

Only generic names are currently listed in the circular, leaving clinicians to question the quality and safety of medications sourced externally.

Compounding the issue, doctors are legally prohibited from directing patients to specific pharmacies, even when certain rare or life-saving medications are known to be stocked only at select outlets.

They note that this limitation undermines the timely administration of critical treatments.

Laboratory medicine ignored

Another major gap, experts say, is the circular’s failure to address laboratory medicine.

With no clear policy for outsourcing unavailable lab tests, the responsibility now falls squarely on hospital directors, placing further pressure on already overburdened administrative teams.

Leave a comment