Sri Lanka’s public sector, long criticized for inefficiency, political patronage, and weak productivity, is under renewed scrutiny as the government announced plans to recruit 75,000 new employees while pledging to “rightsize” the system over the next five years.

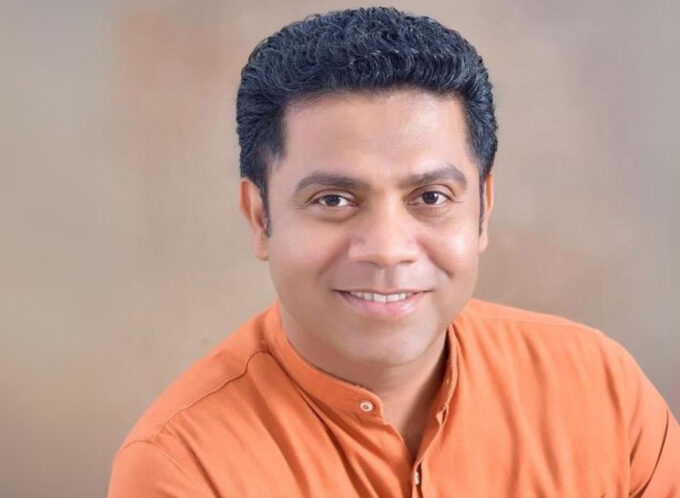

Deputy Industries Minister Chathuranga Abeysinghe, speaking at a Deloitte post-budget forum, acknowledged that the public service is “bloated not at the skilled or executive level, but at the bottom tiers where past governments hired supporters.”

He said that the upcoming intake will focus on critical skill-shortage areas such as nurses, teachers, engineers, and technical professionals.

Sri Lanka’s public sector, encompassing ministries, departments, state-owned enterprises, and statutory boards, currently employs roughly 1.35 million people, approaching an “approved cadre” of nearly 1.5 million.

Analysts note that productivity has not kept pace, particularly among the “Development Officer” cadre, which as of December 2024 numbered 102,681 despite an approved cadre of 77,796.

Many of these officers are posted to district or divisional offices lacking basic resources, and most cannot demonstrate job-related skills, IT literacy, or communication competence, raising questions about their economic contribution.

The public sector’s burden is compounded by Sri Lanka’s large post-war military structure.

Unlike other countries that downsized their armed forces after conflict, Sri Lanka has not carried out systematic demobilization.

Thousands of former personnel remain outside the formal workforce, while tens of thousands who joined between 2006 and 2009 will soon complete 20 years of service.

The government is exploring ways to reskill and integrate these individuals into private industry, entrepreneurship, and technical fields.

Officials say workforce reductions will primarily occur through digitalization and automation rather than compulsory downsizing, with voluntary retirement schemes encouraged.

A slight decline in public sector numbers was recorded in 2024, but inefficiency remains entrenched, prompting middle-class families to increasingly turn to private schools, tuition, and healthcare due to deteriorating public services.

Analysts also cite policy reversals under the Rajapaksa era, including the re-nationalization of formerly privatized enterprises in the sugar sector.

These entities now require substantial state subsidies, further straining public finances.

Leave a comment