By Our Political Editor

Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s interview with Al Jazeera’s Mehdi Hasan has ignited a political firestorm in Sri Lanka, bringing back a decades-old controversy that had once nearly ended his political career.

While his critics have labelled the interview a disaster, others, including long-time political rivals, have rallied behind him, defending his position and questioning the motives of those seeking to revive the past.

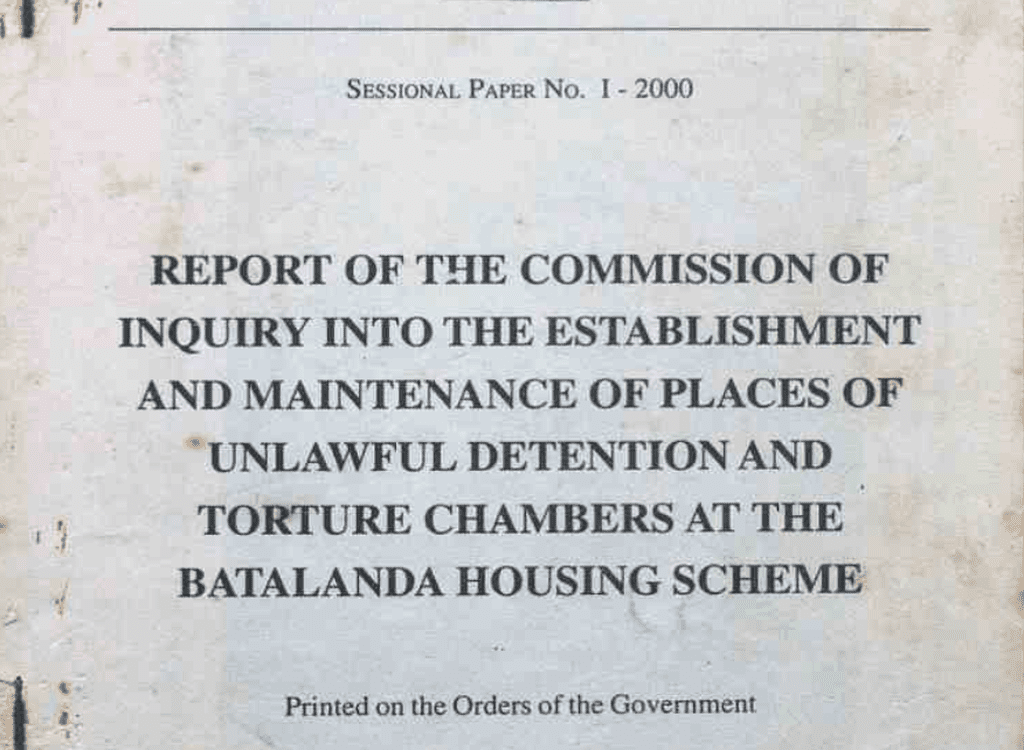

The Batalanda Commission Report, produced during Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s presidency, is the key issue at the heart of the controversy. The report investigated alleged state-sponsored abuses during the brutal 1987–1989 JVP insurrection. The report was never tabled in Parliament, and its recommendations were never acted upon, leaving it as a political weapon that has been wielded against Wickremesinghe at various points in his career.

In the 1999 presidential election, the Batalanda narrative was used heavily against Wickremesinghe. While Kumaratunga ultimately won the election, surviving a suicide attack on the final day of the campaign, Wickremesinghe’s defeat led to internal coups within the United National Party (UNP) against his leadership. He survived, but the shadow of those allegations has never entirely faded.

The latest revival of the Batalanda issue has been spearheaded by the Peratugami Party (Frontline Socialist Party), led by Kumar Gunaratnam and backed by his key allies, Pubudu Jayagoda and Duminda Nagamuwa. Gunaratnam, a key JVP leader during the 1989 rebellion, survived the crackdown due to the intervention of Sarath Fonseka, the man who would later go on to lead Sri Lanka’s military to victory over the LTTE in 2009. Now, Gunaratnam and his faction are aggressively pushing President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s administration to take action against Wickremesinghe, demanding that he be stripped of his civic rights and prosecuted based on the recommendations of the Batalanda Commission.

This pressure has placed President AKD in a challenging position. For the first time in the JVP’s history, the party is in power, not through armed rebellion but a democratic landslide victory. The government is already struggling to manage an increasingly fragile economy, and now it faces an internal political dilemma that could divide its ranks. According to internal sources close to the President, he was firm about tabling the Batalanda report in Parliament.

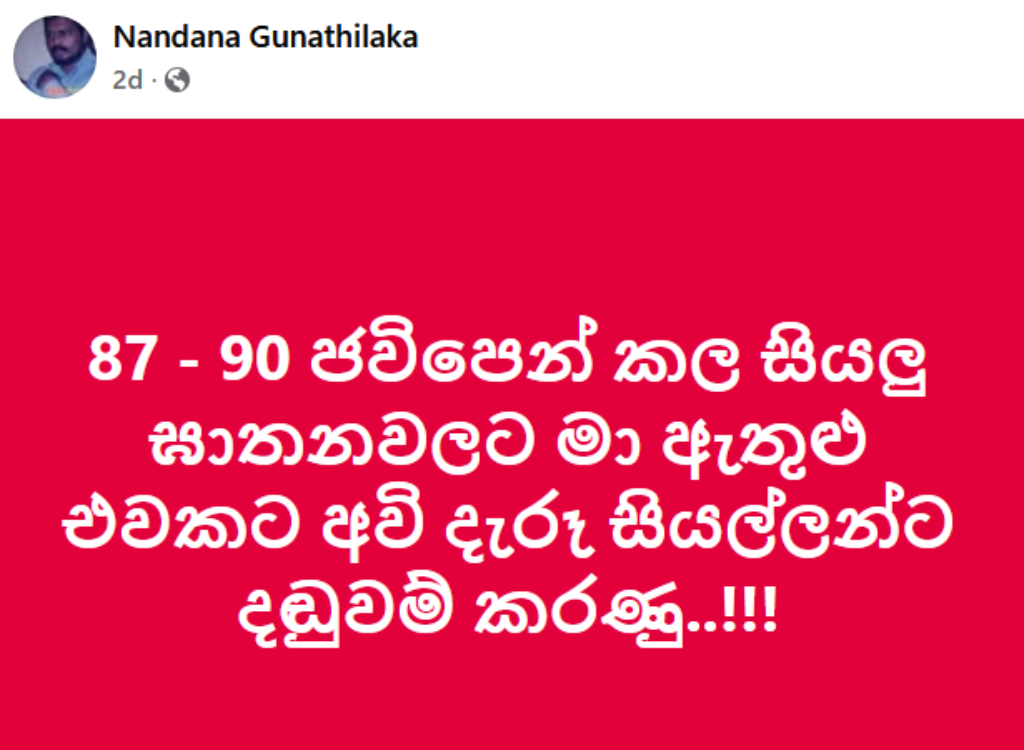

Adding further complexity to the issue is the intervention of Nandana Gunatilake, a former JVP leader and 1989 rebellion survivor, who has now thrown open an entirely new dimension to the debate. Gunatilake, who later defected to the UNP, has publicly stated that justice should not be one-sided and that the excesses of both the government and the JVP during the rebellion should be pursued. His willingness to testify could completely shift the conversation, potentially exposing actions from both sides of the conflict that many would prefer to remain buried in history.

For Wickremesinghe, this is a fight he appears ready to take on. According to sources close to him, he has already signalled his willingness to engage in a prolonged legal battle if necessary, one that could stretch across President AKD’s entire term. This would ensure that Batalanda remained in the headlines for years, keeping Wickremesinghe politically relevant while forcing the government into a drawn-out, highly divisive legal and political confrontation.

President AKD, unmoved by the political and legal challenge ahead, handed over the honours to the leader of the house, the JVP firebrand, and senior cabinet minister Bimal Ratnayake to table the Batalanda Commission Report on Friday morning in the parliament. Ratnayake was calm, determined, and emotional throughout his speech. He whitewashed the JVP excesses and crafted the narrative against J.R Jayewardene/Ranasinghe Premadasa administrations for brutality and excesses. Further, he was critical of former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga for playing politics with innocent people’s lives for the sake of power. Ratnayake declared the intention of President AKD to see through the justice while notifying the attorney general to proceed with necessary legal actions and appointing a special committee to advise on the route to pursue. Ratnayake further echoed that the government will allow a two-day Parliamentary debate on the above mentioned issue.

As the Batalanda issue consumes national discourse, the government is overwhelmed on multiple fronts. The AKD administration is already battling the complexities of governance, facing a fragile economy, and trying to maintain its political credibility amid mounting challenges. The past two weeks have seen the government engaged in a relentless narrative war against a fugitive Inspector General of Police, Deshabandu Tennakoon, who remains elusive despite legal action.

Adding to the turmoil, Ven. Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara Thero has intensified his campaign against what he calls the growing radicalisation of Islamist groups, positioning himself as the protector of Buddhism. His aggressive rhetoric has captured significant media attention, further complicating the government’s political stage. The administration now faces a dilemma in handling the firebrand monk, whose growing influence could either serve as a political asset or a destabilising force.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya continues to face relentless political attacks, with critics questioning her leadership and attempting to undermine her credibility. The government’s internal missteps, including contradictory statements from key political leaders, including the Premier, and ill-considered remarks from ruling party members, have only worsened the situation, exposing weaknesses in its communication strategy.

Against this chaotic backdrop, the Batalanda controversy is fueling the fire, pushing the government to fight hundreds of battles simultaneously.

The stakes for the AKD administration are incredibly high. The JVP has worked for decades to transition from a revolutionary force into a legitimate governing party. Reviving Batalanda could either reinforce the party’s commitment to justice or trap it in a never-ending political vendetta that distracts from its governance agenda.

The coming weeks will be crucial in determining how this unfolds. With local government elections to be held in May, the washing of sins of both sides will be a political spectacle. There is a risk for all parties; Wickremesinghe is in the spotlight, and his executive President during the 89 rebellion, Ranasinghe Premadasa, was the commander in chief, crushing the rebellion. The junior Premadasa is the current leader of the opposition. He will have to defend his father, too. Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, widely accused of war crimes against the LTTE, is in the hot seat. And all eyes will be on former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, the architect of the Batalanda Commission Report. It’s widely known that her Husband, Vijaya, was killed by the JVP during the armed rebellion, though there are contradictory narratives regarding the heartthrob’s brutal assassination. The wind can blow however it wishes, but it will be a political and social justice spectacle.

One thing is sure: the Batalanda controversy will not go away anytime soon. If both sides choose to fight, Sri Lanka is in for a prolonged and deeply divisive political war that could reshape the country’s political future for years to come.

Leave a comment