By Center for Policy Alternatives

What is the Prevention of Terrorism Act?

The Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) was enacted in 1978 as a temporary measure (initially only for 3 years) but was made permanent in 1982. It introduced offences previously not present in the ordinary law which were and are being abused with serious human rights implications for the nearly half century in which it has been in operation. Most noticeably, section 2(1)(h)[1] has been severely misused to crush legitimate dissent and target human rights activists, journalists and politicians.

The PTA allowed for prolonged detention of suspects without having to even produce them before a judicial officer and for the admissibility of confessions to prove the case. The law as a whole, and these provisions in particular, encouraged a culture of torture in order to obtain confessions from suspects, with very little other evidence. The widespread use of torture in the context of suspects arrested under the PTA has been well-documented, including by the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka.

The PTA was hurriedly passed by Parliament and included many provisions that were clearly in violation of several Fundamental Rights guaranteed by the Constitution with limited oversight and has led to a culture of impunity.

How is the PTA a valid law if it violates certain Constitutional protections?

When an ordinary law (that is, a Bill other than a constitutional amendment) is challenged before the Supreme Court, the Court may arrive at one of three determinations.

| First, it may hold that the Bill is consistent with the Constitution, in which case the Bill may be enacted by a simple majority in Parliament. | Second, the Court may find that the Bill is inconsistent with the Constitution but does not violate any entrenched provisions; in such circumstances, the Bill may be passed only with a special majority (2/3 the total number of members – i.e. 150 votes in its favour). | Third, the Court may determine that the Bill is inconsistent with one or more entrenched provisions of the Constitution, in which event the Bill can be enacted only with both a special majority in Parliament and the approval of the People at a referendum. |

The Sri Lankan Supreme Court has commented on this problem especially in the context of the PTA. The Supreme Court said in Weerawansa v Attorney General (2000) 1 SLR 387:

“When the PTA Bill was referred to this court, the court did not have to decide whether or not any of those provisions constituted reasonable restrictions on Articles 12 (1), 13 (1) and 13 (2) permitted by Article 15 (7) (in the interests of national security etc), because the court was informed that it had been decided to pass the Bill with two-thirds majority. The PTA was enacted with two-thirds majority, and accordingly, in terms of Article 84, PTA became law despite many inconsistencies with the constitutional provisions.”

What is an Urgent Bill and why was the PTA passed as an urgent bill?

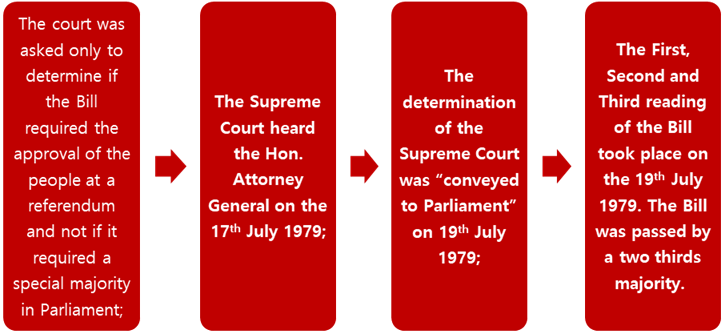

In 1979, the government of the day had a special majority in Parliament. The PTA was introduced as an urgent Bill, a procedure that significantly curtailed the time available to the Supreme Court to review its constitutionality and limited opportunities for public engagement and scrutiny. The government further informed the Court that it intended to pass the Bill with a special majority in any event, thereby effectively inviting the Court to consider only whether the Bill was inconsistent with any entrenched provision of the Constitution that would necessitate approval by referendum.

The legislative process pertaining to the PTA can be summarized as follows:

- The Supreme Court had only 72 hours to conduct a hearing, study the Bill, write its decision and communicate this decision to Parliament.

- An urgent bill was not made public, so this meant the public did not have access to the bill before it went to the Supreme Court.

- In the case of the PTA bill, only the Attorney General was heard by the Supreme Court.

- The Court’s assessment of the Bill was likely influenced by these constraints placed on its functions. It was also relevant that, at the time of review, the Bill contained a sunset clause providing that the law would operate for only three years.

- Subsequently, before the expiry of that period, the government introduced an amendment repealing the sunset clause alone. While presented as a limited change, this amendment materially altered the character and effect of the law by rendering permanent a law that had originally been enacted as temporary.

What this means is that the PTA should not be treated as an appropriate yardstick when reviewing or analysing reforms to Sri Lanka’s counter-terrorism framework. While any new legislation must, at a minimum, provide stronger safeguards against abuse than those found in the PTA, mere improvement over the PTA is insufficient. A replacement or reforming law must itself be fully consistent with the Constitution, in particular the fundamental rights guaranteed therein, and must also comply with applicable international human rights standards.

What has the present government promised in terms of PTA reforms?

| At page 127 of its 2024 manifesto (English version), the National People’s Power (NPP) committed to the “abolition of all oppressive acts including the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and ensuring civil rights of people in all parts of the country.” This statement constitutes an explicit recognition by the NPP that the PTA is an oppressive law and reflects a clear commitment to its repeal. At the same time, it underscores the party’s pledge to safeguard and promote the civil rights of all people throughout the country. | In early 2024, President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government introduced legislation intended to replace the PTA, titled the Anti-Terrorism Bill (ATB). This proposed law was challenged before the Supreme Court. Notably, the first petitioner in that challenge was Hon. Vijitha Herath, who now serves as Minister of Foreign Affairs, while the second petitioner was Hon. Wasantha Samarasinghe, who is presently a Minister in the NPP government. These petitioners contended that key provisions of the Bill violated constitutionally guaranteed fundamental rights. |

As with the government in power in 1978, which enacted the PTA, the present government enjoys a special majority in Parliament, enabling it to repeal the PTA with relative ease. In light of this mandate and parliamentary strength, a high standard must be expected of the government in advancing its reform agenda, particularly in dismantling oppressive legislation and replacing it with laws that are constitutionally sound and rights-respecting.

What have other recent efforts to amend/ repeal the PTA been?

Prior to the introduction of the present proposed legislation, there have been three significant attempts over the past decade to reform or replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as seen in the table below. These efforts reflect a growing recognition by successive governments that this draconian law must be dismantled, driven both by sustained international pressure and by its increasing unpopularity among the Sri Lankan public.

| 2018 | The first such effort occurred when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, then under the leadership of the late Mangala Samaraweera, published the Counter Terrorism Bill (CTB). The CTB proposed substantial changes to Sri Lanka’s counter-terrorism legal framework and, in several respects, represented an improvement on the PTA. Nevertheless, the Bill was widely criticised for failing to meet international human rights standards. It was challenged before the Supreme Court, which found certain provisions to be unconstitutional. Ultimately, the Bill was not enacted, as the country was soon engulfed in a series of destabilizing events, most notably the Easter Sunday bombings of April 2019, which significantly reshaped public discourse on terrorism and national security. |

| 2022 | The second attempt was made when amendments to the PTA were enacted. While these amendments mitigated the practical effect of some of the most oppressive provisions of the Act, they adopted a largely minimalist approach. The reforms introduced were widely regarded as insufficient to address the lived realities of those affected by the PTA. Many areas identified as requiring urgent reform by legal scholars, civil society organisations, and even the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka were left untouched. In this context, the 2022 amendments were viewed by many as a tokenistic response aimed at easing international scrutiny rather than a genuine effort to confront the systemic abuses and violations associated with the PTA. |

| 2023/ 2024 | The third attempt emerged when the government sought to replace the PTA through the Anti-Terrorism Bill (ATB). This Bill broadly mirrored the structure of the 2018 CTB, though several of its more progressive provisions were either diluted or removed. Notably, the ATB was introduced in the aftermath of the 2022 Aragalaya protest movement, and the expansive definitions of terrorism contained in the Bill appeared calibrated to prevent the re-emergence of similar mass mobilisations. An initial draft Bill was published in early 2023 and was met with widespread criticism, leading to its withdrawal. Although the government subsequently claimed to have conducted public consultations, the revised Bill that followed remained substantially similar, with only minor modifications. This version too was challenged before the Supreme Court and was ultimately never enacted. |

[1] Section 2 (1)( h)- any person who by words either spoken or intended to be read or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise causes or intends to cause commission of acts of violence or religious, racial or communal disharmony or feelings of ill-will or hostility between different communities or racial or religious groups;

Leave a comment