By Madhusha Thavapalakumar

Sri Lanka has climbed 14 spots in the 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), inching its score from 32 to 35 and moving up from 121st to 107th globally. That is the country’s best performance in a decade. But scratch beneath the surface and the cracks remain deeply entrenched.

The CPI, published by Transparency International, measures perceived levels of public-sector corruption using 13 independent data sources, including the World Bank and World Economic Forum. Sri Lanka’s latest score is still far below the global average of 43. It remains firmly in the category of countries struggling with persistent institutional weaknesses, unaccountable decision-making, and opaque financial practices.

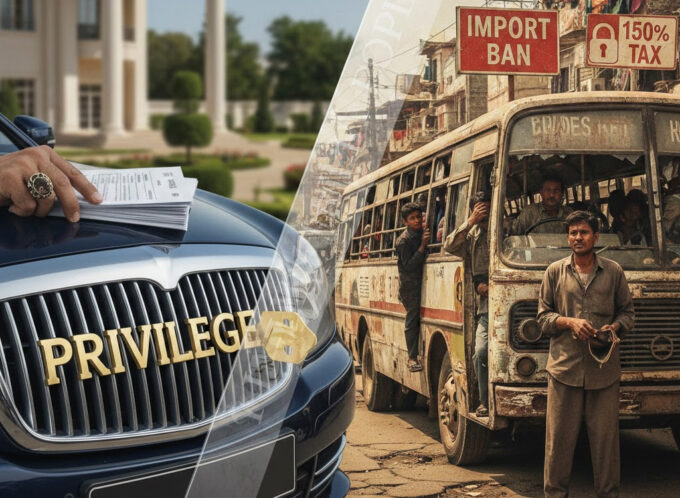

Even as the country’s international image improves incrementally, the lived experience of corruption for ordinary Sri Lankans remains painfully unchanged.

Where the rot begins, and where it costs most

Most Sri Lankans can describe corruption in intimate detail. It’s the “speed money” handed to a public official to move a permit. It’s the favour asked to land a school placement, or the “gift” to keep a file from getting lost. But while these small-scale exchanges are frustrating, they are only the visible layer of a far deeper, more damaging problem.

The more dangerous form of corruption is the institutional kind, the kind that gets embedded into fiscal policy and procurement decisions, often cloaked in the language of “national interest.” These are the decisions that rarely make headlines but drain the economy in ways far more lasting than a single bribe ever could.

One such case was the sugar tax revision of 2020. Overnight, the import duty on sugar was reduced from Rs. 50 to just 25 cents per kilogram. That single act, which remained in place for three years, cost the government over Rs. 16 billion in lost revenue. The decision was made unilaterally by the Minister of Finance, bypassing parliamentary scrutiny.

Then there’s the infamous central bank bond scandal of 2015-2016, where alleged insider trading during bond auctions caused the Treasury an estimated Rs. 8 – 9 billion loss. No money visibly changed hands in public, no envelope was passed under a table, yet the economic fallout reverberated through the financial system for years. The scandal shook investor confidence, damaged the credibility of financial institutions, and contributed to the country’s long-term fiscal stress.

Governance is now a credit issue

Global credit rating agencies are paying close attention to these patterns. According to Fitch Ratings’ quantitative sovereign‑rating framework, governance‑related indicators account for approximately one fifth of the variation in sovereign credit scores. This has real-world consequences. Weak governance means higher borrowing costs. Higher borrowing costs mean deeper debt. And deeper debt means less money for schools, hospitals, and roads.

In its June 2024 Selected Issues paper, “Governance and Growth: Lessons and Policy Implications,”the IMF states that Sri Lanka’s economic crisis exposed deep-rooted governance issues and corruption vulnerabilities that weakened fiscal institutions and economic management. The Fund’s assessment places governance failures within the core drivers of fiscal deterioration and debt distress.

The IMF identifies systemic weaknesses across fiscal governance, revenue administration, public investment management, financial oversight, and rule-of-law institutions. It notes that perception-based governance indicators suggest corruption vulnerabilities intensified between 2012 and 2022. During that period, Sri Lanka’s performance on measures such as accountability, regulatory quality, and control of corruption compared unfavorably with many higher-middle income Asian peers.

The Fund links these governance weaknesses directly to fiscal outcomes. According to the report, deficiencies in revenue administration and tax expenditure management reduced collection efficiency and narrowed the effective tax base. Limited transparency in fiscal decisions and weak accountability mechanisms contributed to declining revenue performance in the years preceding the 2022 sovereign default.

Public investment management is another area of concern identified in the assessment. The IMF highlights transparency and accountability gaps in procurement and project oversight. Weak competitive safeguards, the report notes, can reduce the efficiency of infrastructure spending, raising project costs without commensurate economic returns.

Beyond diagnosis, the IMF attempts to quantify potential gains from reform. Using dynamic modeling, the Fund estimates that comprehensive governance reforms could raise Sri Lanka’s medium-term growth by between 0.6 and 1.2 percentage points annually.

The identified channels include improved tax collection efficiency, stronger public investment management, and reduced distortions affecting private sector activity. These projections are conditional on sustained implementation and coherent sequencing of reforms.

The IMF emphasises that reform effectiveness depends on political ownership and institutional consistency. Fragmented or partial measures, the report suggests, are unlikely to deliver durable macroeconomic benefits. International experience cited in the paper indicates that governance reform yields measurable fiscal and growth improvements when implemented comprehensively and supported by strong enforcement frameworks.

The IMF’s prescription: reform with teeth

In response to these concerns, the IMF has tied its $ 3 billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF) to a set of deep structural reforms. In September 2023, the Fund released a detailed diagnostic, the first such report conducted in Asia, outlining 16 priority recommendations for improving governance and accountability in Sri Lanka. These include:

- Removing ministerial discretion over tax concessions and procurement

- Enacting a comprehensive Proceeds of Crime law

- Publishing a centralised registry of all tax exemptions with cost estimates

- Requiring parliamentary oversight for fiscal decisions that carry revenue impact

- Strengthening the mandate and independence of the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC)

To its credit, Sri Lanka has committed to these reforms through the National Anti-Corruption Action Plan (NACAP) 2025-2029, launched in April 2025 in alignment with IMF benchmarks and monitored by CIABOC, civil society, and international partners like UNDP. Yet implementation lags: key laws on asset declarations and tax incentives remain pending, while CIABOC, despite new powers under the 2023 Anti-Corruption Act, faces resource shortages and prosecutorial delays.

A signal to investors or just more paperwork?

TISL Senior Officer – Advocacy and Research Dhewni Dias speaking to The Morning Money stated that a CPI score improvement signals renewed expectations. The real test now is whether transparency and accountability are strengthened in practice. This requires transparent decision-making, timely and merit-based appointments to leadership positions in key oversight and law enforcement bodies, and ensuring these institutions are insulated from political shifts.

“Bodies such as the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC) and the Right to Information Commission must be adequately resourced, professionally staffed, and granted full operational autonomy to carry out their mandates effectively. Without sufficient financial, technical, and human resources, and without clear independence, true anti-corruption progress risks stagnation.”

She added that governance reform must also extend to strengthening the anti-corruption regulatory framework. Sri Lanka needs modern, transparent public procurement legislation that is properly drafted, debated, and implemented, ensuring competition and safeguards against conflicts of interest.

“Beneficial ownership transparency mechanisms must be fully operationalised so that the true owners of companies are visible and accountable. Political finance regulations require further strengthening and enforcement to prevent undue influence in electoral and policy processes. Critically, accountability mechanisms must move beyond design to consistent implementation.”

At the same time, the continued reliance on repressive legislation such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Online Safety Act undermines transparency and civic oversight, both of which are essential for sustainable accountability, she added.

When corruption becomes economic sabotage

Speaking to The Morning Money, Frontier Research Head of Macroeconomic Advisory Chayu Damsinghe stated that viewing the CPI score as a direct measure of reduced corruption, noting: “By virtue of it being a perception index, it doesn’t necessarily measure corruption itself, but the perceptions of corruption that people have.”

Damsinghe stated that while the CPI uses a specific methodology to assess perceived corruption, the narrow definition may not reflect the full scope or nature of corruption affecting Sri Lanka’s economy.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that corruption has improved or gotten worse or gotten better, but merely that people’s perception of the amount of corruption in Sri Lanka has improved,” he explained.

Perceptions nonetheless carry economic weight. As Damsinghe pointed out, foreign investors often respond to these indicators when assessing risk. “These kinds of indicators definitely affect how foreign investors look at a country,” he said, suggesting that even perception-based improvements could bolster confidence in Sri Lanka’s investment climate.

However, the challenge, he noted, lies in understanding the different forms corruption takes. While high-profile theft and misappropriation dominate public discourse, more systemic and less visible practices, such as policy manipulation to benefit allies, often go unrecognised and unmeasured. “Even in countries like Sri Lanka, the perception of that as corruption doesn’t always come across,” he added.

To illustrate the point, Damsinghe referred to Scandinavian nations often ranked among the least corrupt, noting they still face criticism over opaque bureaucratic decisions. He cited Norway’s wealth fund real estate investments as an example:

He highlighted the case of China, where historically entrenched local government corruption coincided with rapid economic growth.

Over time, that same growth created financial incentives to address corruption. “It’s kind of a two-way street… the improvement of economics that have happened as a result of, let’s say, a corrupt economic model have then resulted in the kind of financial incentives, economic incentives that have later addressed that corruption,” he observed.

A long road ahead, but a path exists

There are glimmers of progress. The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act, enacted in 2023, has been praised for enhancing institutional independence and establishing strong monetary policy frameworks. The Public Financial Management Act now sets a cap on non-interest public expenditure, limiting it to 13% of GDP.

On the tax front, mandatory Taxpayer Identification Numbers (TINs) and efforts to digitise compliance have helped curb evasion. Still, key governance reforms, such as publishing tax incentives, tracking politically exposed persons, and recovering stolen assets, remain works in progress.

Neither the CIABOC nor The Ministry of Justice was available for a comment when The Morning Money reached out. However, Sri Lanka’s anti-corruption efforts gained visibility in early 2026 when CIABOC Chairman Justice Neil Iddawela released the commission’s 2025 Progress Report.

He publicly labeled state-sector corruption a “menace” that siphons public funds and erodes trust in institutions like procurement agencies and revenue authorities. Iddawela highlighted a strategic pivot: from handling 8,409 complaints reactively to launching proactive probes into unexplained wealth and money laundering, enabled by the Anti-Corruption Act No. 9 of 2023.

This follows his earlier September 2025 remarks naming the top 10 corruption-prone institutions, including Customs, Excise, and several ministries, urging systemic fixes beyond arrests.

Sri Lanka’s most costly corruption scandals

Central Bank Bond Scam (2015-2016)

Estimated loss: Rs. 8-9 billion

Alleged insider trading during bond auctions

Sugar Tax Scam (2020-2023)

Estimated revenue loss: Rs. 16 billion

Import tax cut from Rs. 50 to 25 cents/kg

‘Sil Redi’ Scandal (2014)

Rs. 600 million in public funds used for pre-election religious donations

Coal Tender Scandal (2016)

Bypassed competitive bidding for coal imports

Flagged by Auditor General

‘Helping Hambantota’ (2005)

Tsunami aid allegedly diverted to private fund

Source: The Morning Money

Leave a comment