By Center for Policy Alternatives

The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Bill (Bill) was published on the website of the Ministry of Justice[1], and public comments on the Bill have been called for, on or before the 28th of February 2026. This Bill seeks to repeal and replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which was a key campaign promise made by the present government. The following commentary provides an initial analysis of the concerns raised by the Centre for Policy Alternatives in relation to this draft Bill.

How does the Protection of the State from Terrorism Bill compare with the previous attempts to amend/repeal the PTA?

The newly proposed Protection of the State from Terrorism Bill (PSTB) closely resembles the earlier CTB (from 2018) and ATB (from 2023 / 2024) in its overall structure, with certain limited differences that may be characterised as improvements. However, many of the fundamental concerns and criticisms levelled against the earlier drafts persist in the present Bill, raising serious questions as to whether it represents a meaningful departure from the problematic legislative approaches that have characterised previous reform efforts.

What kinds of acts constitute the offence of terrorism under this proposed PST bill?

The offence of Terrorism is contained in clause 3 of the Bill, and it involves intentionally or knowingly committing any act for the purposes contained in clause 3(1) (column 1 below) and causing one of the consequences contained in clause 3(2) (column 2 below).

| Any person who, intentionally or knowingly, commits any act; | |||

| 3(1) For the purpose of; | (a) provoking a state of terror (b) intimidating the public or any section of the public; (c) compelling the Government of Sri Lanka, or any other Government, or an international organisation, to do or to abstain from doing any act; (d) propagating war, or violating territorial integrity or infringing the sovereignty of Sri Lanka or any other sovereign country, | 3(2) Causing the consequence of; | (a) the death of a person; (b) hurt; (c) hostage-taking (d) abduction or kidnapping; (e) serious damage to any place of public use, any public property, any public or private transportation system or any infrastructure facility or environment; (f) committing the offence of robbery, extortion or theft, in respect of the public or private property (g) serious risk to the health and safety of the public or a section of the public; (h) serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with, any electronic or automated or computerised system or network or cyber environment of domains assigned to, or websites registered with such domains assigned to Sri Lanka; (i) the destruction of, or serious damage to, religious or cultural property; (j)serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with any electronic, analogue, digital or other wire-linked or wireless transmission system, including signal transmission and any other frequency-based transmission system; or (k) without lawful authority, importing, exporting, manufacturing, collecting, obtaining, supplying, trafficking, possessing or using- (i) firearms, offensive weapons, ammunition, explosives; or (ii) any article or thing used or intended to be used in the manufacture of explosives or combustible or corrosive substances; or (iii) any biological, chemical, electric, electronic or nuclear weapon, other nuclear explosive device, nuclear material, radioactive substance, or radiation-emitting device. |

When reading the purposes in column 1 and the consequences in column 2 together, some combinations that can amount to terrorism are clearly very broad. For example –

| For the purpose of compelling the government of Sri Lanka to do something (eg, to reduce electricity tariffs) doing an act which results in theft (eg, taking sign boards announcing the tariffs placed in public places). | Compelling an international organization to do something (eg demanding that the UN takes action on the occupation in Palestine) doing an act which results in hurt (eg slapping a police officer who tries to prevent the protest). |

While these may be offences that are punishable under other laws, including such a wide scope of offences is broad, and can have the effect of stifling dissent.

There seems to have been some acknowledgment by the drafters of this law that the broad nature of this clause can impact dissent in the form of protest. Clause 3(4) has thus been included, to say ‘The fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy or dissent or engages in any strike, lockout or other industrial action, is not by itself a sufficient basis for inferring that such person- (a) commits or attempts, abets, conspires, or prepares to commit the act with the intention or knowledge specified in subsection (1); or (b) is intending to cause or knowingly causes an outcome specified in subsection (2)’. However, this exclusion is vague, and does not provide much clarity on when a protest may be considered ‘an act of terrorism’.

What are some of the other offences under the proposed PST bill?

Other offences include;

| Clause 8 Acts associated with terrorism (inter alia harboring or concealing a person who has committed an act of terrorism, or supplying information to a person for an act related to terrorism) | Clause 9 Encouragement of terrorism (inter alia publishing or speaking any statement that may encourage the commission of an act of terrorism) | Clause 10 Dissemination of terrorist publications (inter alia distributing a possessing a terrorist publication) | Clause 12 Training for terrorism | Clause 15 Failure to provide information (inter alia failing to provide a police officer information about a person who has committed and offence under the act, or their whereabouts) |

All of these offences are expressly linked to the offence of terrorism set out in clause 3. Consequently, the excessively broad definition of terrorism contained in clause 3 causes these related offences to operate with an unduly expansive reach, capturing individuals whose conduct should not properly be characterised linked to terrorism.

Why is the media concerned by the proposed PST bill?

Taken together, these provisions risk creating a legal framework that unduly restricts freedom of expression, press freedom, and the right to information, and may facilitate the suppression of legitimate journalistic activity under the guise of counter-terrorism.

What is executive detention and how does it work under the proposed PST bill?

Article 13(2) of the Constitution provides that; “Every person held in custody, detained or otherwise deprived of personal liberty shall be brought before the judge of the nearest competent court according to procedure established by law and shall not be further held in custody, detained or deprived of personal liberty except upon and in terms of the order of such judge made in accordance with the procedure established by law.”

Thus, it is constitutionally recognized that detention must be in terms of a judicial order. The PTA makes an exception to this, allowing for detention orders to be made by the Minister of Defense, when he believes a person is connected or concerned with any unlawful activity. Under the PTA, following the 2022 amendment, the initial detention order can run for three months, with extensions up to a year. This remains one of the most controversial provisions in the PTA.

The proposed law too makes provisions for detention orders. Clause 29 provides the procedure for making a detention order –

| First, an application is made to the Secretary to the Ministry of Defense, by the IGP, or an officer not below the rank of DIG who is authorized by the IGP to make such order. The request for an order must be based on one of the grounds contained in subclause (3) which are: (a) to facilitate the conduct of the investigation in respect of the suspect; (b) to obtain material for an investigation and potential evidence relating to the commission of an offence under this Act; (c) to question the suspect in detention; or (d) to preserve evidence pertaining to the commission of an offence under this Act. |

| If the Secretary to the MOD is satisfied that reasonable grounds exist, then they can authorize the detention, recording the reasons for doing so. |

| A copy of the detention order must be served on both the suspect and the next of kin of the suspect within a period of 48 hours. |

| The initial detention order can be issued for a period of up to two months. Thereafter, based on the same procedure for request and approval, it can be extended two months at a time, with the maximum period of detention being a year. |

| In terms of Clause 35, an extension of the detention period beyond the initial 2 months requires the approval of a magistrate (however, due to vague drafting this clause is susceptible to being ignored). |

| The power to issue detention orders is vested with the Secretary to the Ministry of the Minister of Defense, similar to the PTA, where the Minister has broad powers in relation to Detention Orders. Despite the fact that a Magistrates approval is required for extensions beyond a period of 2 months, a continued attempt to include executive detention in our law raises serious concerns. |

This Clause also specifies that detention orders should be issued solely for the purposes specified and where necessary. While setting out such circumstances can mitigate potential abuse of Detention orders, the circumstances listed are broad and still make leeway for abuse.

While executive detention can last for up to a year, the total period of detention and remand prior to an indictment being served, in total, can extend to two years. This means that persons may be deprived of their liberty for two entire years before it is even decided that there is a basis to proceed in a case against them.

Will confessions be admissible under the proposed law?

| Law | Ordinary Law/ General Law | PTA | PST Bill |

| Admissibility | Section 24 & 25 of the Evidence Ordinance does not allow for confessions made to police officers to be used in a criminal trial. | Allows confessions to be admitted in evidence even when they are made while the accused is in police custody and in the absence of a Magistrate. | A confession made to a Magistrate may be admissible in evidence, subject to the fulfilment of several procedural safeguards. |

| Rationale / Safeguard | This is a general principle of evidence seen widely across other countries / jurisdictions. This rule is grounded in the understanding that confessions obtained in police custody are frequently influenced by coercion, intimidation, or other forms of improper pressure. | Departs from this well-established safeguard. | The Magistrate is required to inform the suspect of their legal rights and to satisfy themselves that the statement is being made voluntarily. In addition, the Magistrate is mandated to refer the suspect for examination by a Judicial Medical Officer (JMO), both prior to and following the recording of the statement. (clause 60) |

| Role of Police | Restricted. | High level of control. | Statement recorded by the Magistrate on the application of the Police. (clause 60) |

Notwithstanding these procedural protections, a significant risk remains. The initiation of the process rests entirely with the police officer, who may present a suspect to a Magistrate for the purpose of recording a confession that would thereafter be admissible against that individual. In the context of legislation that permits prolonged periods of detention —including continued detention after the statement has been recorded—and where judicial oversight is limited to inspections by a Magistrate at intervals of up to two weeks, there exists substantial scope for coercion. Such coercion may occur in forms that do not necessarily manifest as physical injuries or other indicators detectable in a JMO examination.

In light of the historical experience and enduring legacy of the PTA, including the documented prevalence of coerced confessions, it is recommended that the admissibility of confessions made by persons while in police custody should be excluded altogether. The retention of any exception to these principal risks perpetuating practices that undermine voluntariness, due process, and the right to a fair trial.

Are the dangers of torture in custody mitigated under the proposed law?

It is well documented that in the context of the PTA, torture and other forms of ill-treatment are the norm rather than the exception, with a consistently high incidence of torture having been documented among suspects and accused persons detained under its provisions. Any successor legislation must therefore adopt safeguards that go well beyond minimum standards, as it carries the additional burden of dismantling a decades-long culture of torture and abuse within law enforcement institutions.

The proposed legislation introduces certain protective measures aimed at mitigating this risk. Clause 31 requires a Magistrate to visit an approved place of detention at least once a month, during which the Magistrate is expected to interview detainees and inquire into their welfare. Clause 37 further mandates that a suspect be produced before a Magistrate every fourteen days for the duration of a detention order. In addition, clause 34 grants the Human Rights Commission access to approved places of detention.

Notwithstanding these measures, they operate within a broader framework that continues to permit prolonged periods of detention, allows for the admissibility of confessions in certain circumstances, and enables delays of up to three days before a suspect is first produced before a Magistrate following arrest. In an environment where torture has been widespread and systemic, these structural features significantly weaken the effectiveness of the proposed safeguards.

Against this background, the Bill falls short and does not to meaningfully prevent torture or ill-treatment. Without stronger, more immediate, and more independent oversight mechanisms—particularly at the earliest stages of detention—the legislation risks perpetuating practices that it ought to decisively eliminate.

Will there be continued militarization in the country if this law comes in to force?

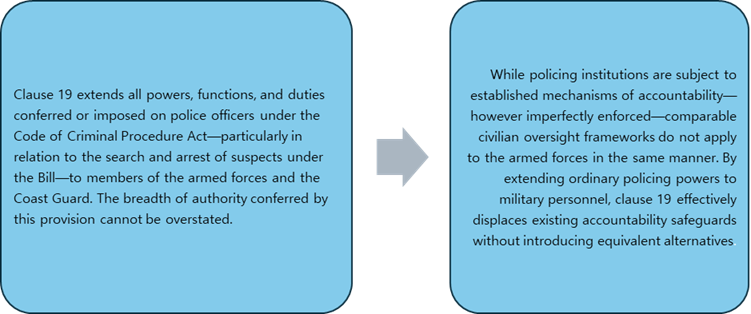

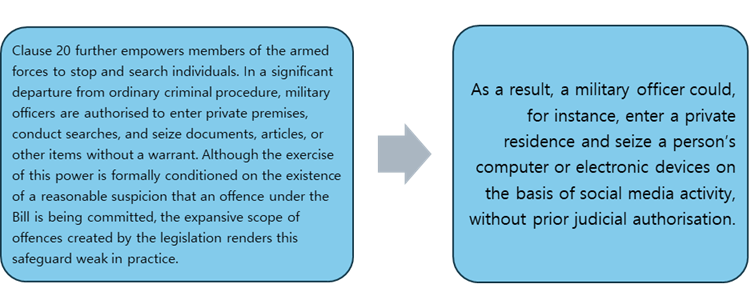

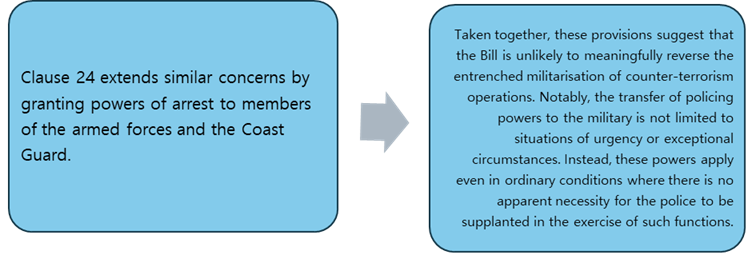

Under the proposed PST bill, the armed forces continue to play a substantial role in law enforcement functions traditionally exercised by the police.

The normalisation of military involvement in routine law enforcement under this framework raises serious concerns regarding proportionality, civilian oversight, and the long-term implications for the rule of law.

What powers does the President get under the proposed law?

Proscription Orders

The proposed legislation grants the President extensive powers to proscribe organisations under clause 63. Clause 63(1) authorises the President to declare an organisation proscribed if he believes it is engaged in an offence under the Act or is acting in an unlawful manner prejudicial to the national security of Sri Lanka or any other country. This provision vests broad discretionary authority in the executive, with limited safeguards against misuse.

The consequences of a proscription order are significant. Under clause 63(2), the President may prohibit specified activities, including the publication of printed or online material in furtherance of the organisation’s objectives. Such restrictions directly implicate freedom of expression and risk suppressing public debate. In addition, clause 6 criminalises a wide range of conduct linked to a proscribed organisation. Individuals may be held criminally liable for broadly defined forms of “association,” such as participating in activities or events, harbouring members, or espousing the organisation’s cause. This significantly expands the scope of criminal liability beyond direct involvement in criminal acts.

When these provisions operate together, they create a powerful mechanism that may be used to suppress dissent. The vague reference to organisations acting in a manner prejudicial to national security lacks clear limiting principles and is open to abuse. As a result, the framework risks infringing fundamental rights and may be used to target lawful advocacy, including human rights work.

Curfew Orders

Clause 65 of the proposed legislation grants the President broad powers to impose curfew orders that exceed those available under the Public Security Ordinance (PSO). Unlike the PSO, curfews issued under the Bill may extend to the whole or any part of Sri Lanka, including territorial waters and airspace, significantly expanding their geographic reach.

The grounds for imposing a curfew are also framed in expansive terms. Clause 65 permits curfews for the protection and maintenance of national security, public security, public order, or public safety. As curfews directly restrict the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of movement, such powers should be subject to strict requirements of necessity, proportionality, and clear connection to a defined threat. These safeguards are not reflected in the current drafting.

By comparison, clause 81(2) of the Anti-Terrorism Bill provided a more detailed and limited set of grounds for curfews, offering greater clarity and restraint. The absence of similar limiting language in clause 65 represents a reduction in safeguards.

Although clause 65(3) limits each curfew to twenty-four hours and requires a minimum interval between successive curfews, it sets no overall cap on cumulative duration. This allows curfews to be repeatedly renewed over extended periods, heightening the risk of disproportionate and abusive use of executive power.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of this publication.

Leave a comment