By Vox Civis

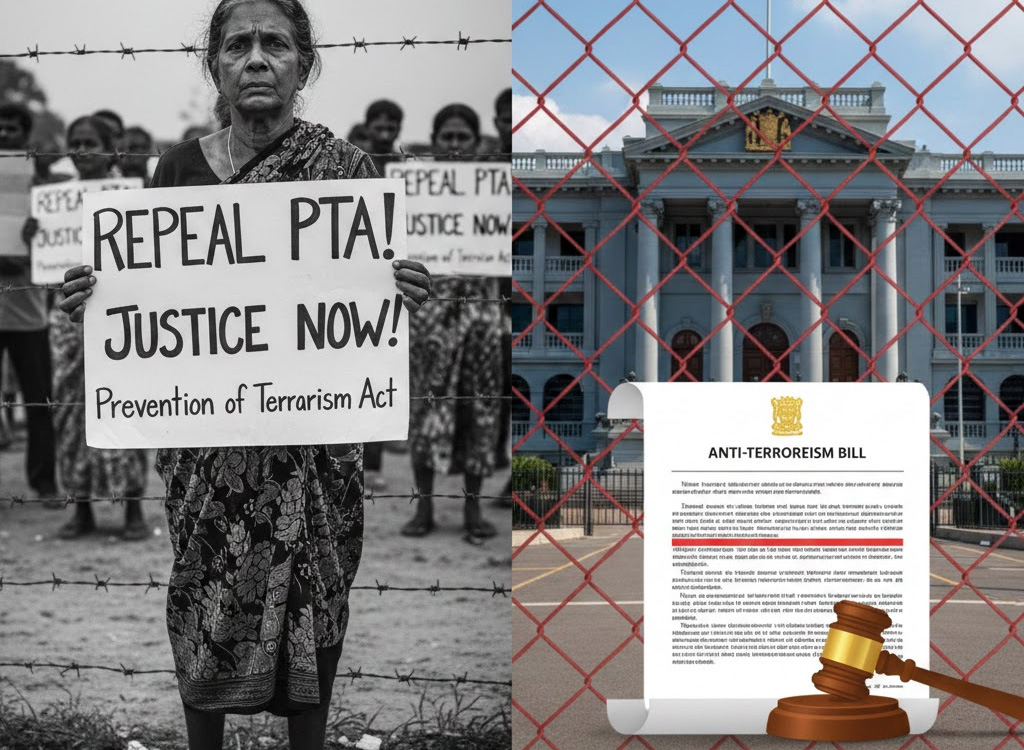

The Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), unveiled in December 2025 as the National People’s Power (NPP) government’s long-promised replacement for the notorious Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTS), was meant to signal a decisive break with Sri Lanka’s authoritarian past. It was sold as evidence of the much promised “system change”: a recalibration of security and liberty after decades in which extraordinary laws hollowed out the rule of law, devastated minority trust and normalised executive impunity.

Instead, the draft has rapidly become a lightning rod for condemnation. From the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) to religious leaders, academics and civil society coalitions, the consensus is that this is not reform but restrengthening and rebranding of an old and dangerous law that also conveniently doubles up a convenient dissent control tool for the governing party.

History has ample evidence of it and if the zest with which the current regime is pursuing the so-called reform is any indicator, the future is unlikely to be any different. What has been placed before the country is not a post-PTA legal architecture, but what critics have aptly labelled PTA+ or PTA Version 2.0 – an expanded, modernised and in most respects, more dangerous iteration of the very system it promised to dismantle.

Vague definition

At the core of the controversy lies the definition of terrorism itself. In any democratic society, counter-terrorism law is exceptional by nature, tolerated only insofar as it is narrowly tailored to address extreme violence aimed at terrorising populations or coercing states through fear. International human rights law, reflected in UN standards and special rapporteur guidance, insists on precision.

Terrorism by definition, must necessarily involve serious violence against persons, coupled with a specific intent to spread terror or intimidate the public. The PSTA abandons this discipline. It creates no less than 13 categories of acts carrying the taint of terrorism, sweeping within its ambit conduct that ranges far beyond the universally accepted understanding of the crime.

Property damage, theft, robbery, interference with electronic systems, and vaguely defined acts such as “violating territorial integrity” are all capable of being branded terrorism offences under the proposed new law. The effect is not merely semantic: by breaking up the distinction between terrorism, ordinary crime, and civil disobedience, the draft dissolves the legal firewall that is meant to protect democratic activity from the most severe forms of criminal sanction. Clause 3(4), often cited by government defenders as a safeguard for protest, rings hollow on close examination.

While it states that protests, advocacy, dissent, or strikes ‘by themselves’ are insufficient to infer terrorist intent, this protection evaporates the moment authorities allege an intent to “intimidate the public” or “compel the government.” These terms are left undefined, granting the state wide latitude to recast mass mobilisation, labour action, or disruptive protest, as terrorism.

For all intents and purposes, Sri Lanka has already been there, done that and regretted it. Which is the very reason that the need arose to do away with the PTA in the first place – a standard election promise of almost every political party, for decades. The JVP turned NPP was the loudest voice that called for its abolition while in opposition, but the trappings of power coupled with dwindling popularity seems to have drastically amended its perception of the law. The shift from opponent to proponent, has thus, been swift.

Potent risk of abuse

Sri Lanka does not have the luxury of treating the risk of abuse of the new law as hypothetical. Past experience of the PTA era demonstrates how elastic definitions become tools of repression. Student movements, trade unions, journalists, and minority activists have repeatedly found themselves on the wrong side of counter-terror laws not because they posed existential threats to the state, but because they embarrassed, challenged, or inconvenienced those in power. The PSTA, far from learning from this history, only reproduces the same structural flaw: a definition so vague and overbroad that it invites abuse.

This problem is compounded by the draft’s treatment of intent. Instead of requiring proof of a calculated purpose to terrorise, the PSTA allows such intent to be inferred from consequences alone. Death, injury, or disruption can suffice, even if the alleged perpetrator had no design to instill terror in the public. This dramatic lowering of the mental threshold strikes at the heart of criminal justice principles. It is precisely this move – from intention to inference, that too by police officers – that transforms exceptional law into a dragnet. With a politicised police, the consequences of this law need no explanation.

If the definition of terrorism is the statute’s conceptual foundation, detention without charge remains its most fearsome operational weapon. One of the foremost electoral promises made by the NPP was the abolition of Executive detention, a power that has cast a long and bloody shadow over Sri Lanka’s post-independence history. Yet the PSTA not only preserves it but also expands it. The Secretary to the Ministry of Defence is empowered to issue detention orders at the request of senior police officers, sidelining the judiciary.

While defenders point to shorter initial detention periods compared to the PTA, this is a triumph of arithmetic over substance. Through extensions and parallel mechanisms, a suspect can remain in custody without formal charge for periods stretching up to two years. During this time, judicial oversight is largely procedural. Magistrates are not invited to ask the most fundamental question as to whether there is credible evidence of a terrorism offence but are instead confined to reviewing paperwork and timelines. Due process is replaced by administrative discretion.

Grim record

Sri Lanka’s grim record of custodial torture and enforced disappearances lends this issue a chilling immediacy. Abuses have flourished precisely in spaces beyond effective judicial scrutiny. The PSTA not only fails to close these spaces but legitimises them. The draft authorises detention in “approved places,” a euphemism that echoes decades of trauma.

Most alarming of all is the provision allowing individuals already remanded by a court to be transferred back into police custody under a detention order issued by the Defence Secretary. This inversion of the criminal justice process of moving from judicial to Executive custody, defies both logic and legality. It creates an express pathway back into environments where coercion thrives.

Equally troubling is the Bill’s overt militarisation of law enforcement. Arrest, search, and detention powers traditionally exercised by the police are extended to the Armed Forces and the Coast Guard. Military personnel are authorised to act on “reasonable suspicion”, a notoriously pliable standard, and are granted a 24-hour window before handing detainees over to the police. In a country where emergency powers have repeatedly blurred the line between civilian policing and military control, this provision signals the normalisation of a permanent security state. Critics have rightly described it as a state of emergency by stealth.

The PSTA also reflects a decisive turn toward the architecture of a surveillance state. Mandatory reporting provisions criminalise the failure to provide information about suspected terrorism, exposing doctors, lawyers, journalists, and clergy to severe penalties for honouring professional ethics or protecting sources. The law goes further still, criminalising the failure to report “misleading information”, a phrase so nebulous that it risks weaponisation against anyone who challenges official narratives.

License to eavesdrop

In the digital realm, the Bill empowers authorities to intercept communications, compel service providers to hand over data, and force the decryption of electronic devices. Sections authorising magistrates to sanction the unlocking of encrypted devices strike directly at the right to privacy protected under international law.

In an age where journalism, activism and political organising rely heavily on secure digital communication, these provisions threaten to suffocate dissent at its source. Clause 10, dealing with terrorist publications, is so expansive that even providing a service enabling someone to “look at” prohibited material may attract liability. Internet service providers, libraries, media houses, and social media platforms are all placed squarely in the line of fire.

Another deeply controversial feature is the revival of “rehabilitation” as an alternative to prosecution. Under the PSTA, the Attorney General may defer criminal proceedings for up to 20 years if a suspect agrees to undergo a specified rehabilitation programme. In theory, this is presented as a humane alternative to punishment. In practice, it amounts to repression by other means.

There is nothing voluntary about an agreement entered into under the threat of prolonged detention and draconian sentences. Rehabilitation becomes a euphemism for extrajudicial punishment: incarceration without conviction, and imposed without the safeguards of a fair trial.

It is against this backdrop that the response of the legal profession and civil society must be understood. The Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) has been unequivocal in its objections, noting that many of the most toxic elements of the aborted 2023 Anti-Terrorism Bill survive in the current draft. The BASL insists on a definition of terrorism aligned with international standards, the removal of ‘recklessness’ as a basis for criminal liability in speech-related offences, and the complete abolition of Executive detention. These are not radical demands; they are the minimum conditions for a law that claims fidelity to constitutionalism.

Incompatible with democracy

Civil society groups have gone further, warning that the PSTA entrenches a surveillance-heavy, militarised model of governance incompatible with democratic norms. A coalition of academics and activists has cautioned that the Bill will corrode trust, particularly among minorities who have borne the brunt of this very law in the past. Religious leaders and the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) have echoed these concerns, warning that the Bill risks reopening wounds that have barely begun to heal.

The government’s decision to open a two-month consultation window does little to allay these fears. Consultation, without a willingness to withdraw and rethink, becomes a performative exercise. Critics are not calling for cosmetic amendments but for a fundamental reset: the withdrawal of the Bill and the publication of a White Paper that makes a transparent, evidence-based case for any specialised counter-terrorism framework.

At its deepest level, the controversy over the PSTA is not merely about clauses and sections. It is about the kind of state Sri Lanka aspires to be after decades of conflict, authoritarian drift, and institutional decay. Counter-terrorism law sits at the fault line between fear and freedom. When drafted with care, it can protect lives without corroding liberty. When drafted in haste or bad faith, it becomes an instrument through which the state terrorises its own citizens.

The December 2025 draft chooses the latter path. It pours old wine into a new bottle, modernising repression with digital surveillance, militarised policing, and administrative detention while retaining the philosophical core of the PTA. In doing so, it betrays not only an electoral promise but a historic opportunity.

The collective opposition has its work cut out to take this chilling message to the people who inevitably will be the ones at the receiving end. Failure to do so now and shouting from rooftops after the event, will amount to no less than dereliction of duty, something the electorate – especially the minority communities – will be unwilling to forgive. The collective opposition and civil society must insist on the immediate withdrawal of the Bill in its present form. Sri Lanka does not need a stronger terrorism law; it needs a smarter, narrower, and more principled one. Until that lesson is learned, every promise of ‘system change’ will ring hollow, drowned out by the familiar echo of a state that still does not trust its own people.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of this publication.

Leave a comment