By Vox Civis

On September 24th, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake addressed the United Nations General Assembly for the first time. The occasion was doubly significant: it was not only his maiden appearance at the world’s largest diplomatic stage, but it also marked his first anniversary as Sri Lanka’s ninth Executive President.

His speech carried the familiar theme that brought the National People’s Power (NPP) to power a year ago; the battle against corruption. “Corruption has eaten into the heart of nations,” he warned the Assembly, insisting that defeating it was key to building a just and prosperous future. He also spoke with passion about global poverty, portraying himself as one deeply concerned about inequality. Yet, for all the lofty words spoken under the bright lights of the UN Headquarters, the ground reality back home could not be more different.

One year into office, President Dissanayake and his government find themselves accused of precisely the same sins they vowed to eliminate. From allegations of ‘tender benders’ and shady contract allocations, to questionable container releases at the port, to undeclared perks for corporate friends and the seemingly massive personal wealth accumulation of ministers, the NPP stands uncomfortably at the receiving end of the very accusations it once hurled at others.

The dissonance between what was said in New York and what is unfolding in Colombo exposes not just political hypocrisy, but something far deeper: the ease with which reformist movements are seduced by the very system they vowed to destroy. In just twelve months, the party that campaigned on the promise of ‘system change’ seems to have become indistinguishable from the system itself.

The Poverty Paradox

In his UN speech, Dissanayake waxed lyrical about poverty. “Poverty, a tragedy as old as human civilization,” he declared, “casts an oppressive shadow on our future. This Assembly must pay special attention to eradicate extreme poverty.” He even quoted Harry Truman of all people, a Cold War-era American President and unapologetic capitalist, in a flourish that baffled many of his Marxist followers.

But back home, poverty is not a rhetorical flourish, it is a lived reality that has grown sharper in the year the NPP has been in power. The World Bank estimates that 30% of Sri Lankans now live in poverty – a figure higher than ever before. Food inflation, reduced real wages and an aggravating cost-of-living crisis have pushed families who were once middle class into destitution. For the poor, the last year has not been a period of relief, but of deeper struggle.

The government’s initiatives to address poverty remain thin. Welfare programmes have been mired in administrative confusion leaving thousands excluded. Fuel and electricity tariff increases have disproportionately burdened the poor, while subsidies have been slow to materialise. The “new economic dawn” promised by the NPP looks more like an old nightmare in a fresh disguise.

The irony of quoting Truman – a leader who famously enshrined the American capitalist project – highlights another paradox. In the name of pragmatism, Dissanayake seems willing to discard the ideological purism that made him distinctive. But if Marxists start sounding like capitalists abroad while failing to deliver bread at home, their credibility will be in question.

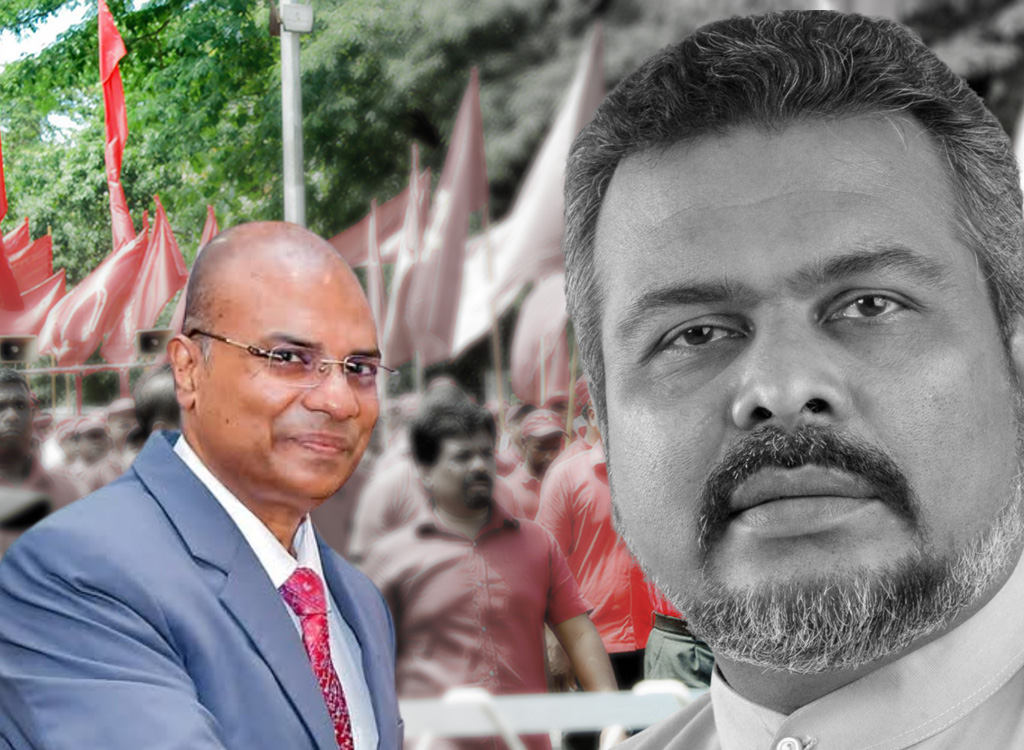

Minister who redefined bribery

If the President’s international speech revealed lofty aspirations, his ministers’ utterings at home revealed troubling realities. Just hours before Dissanayake’s UN address, one of his most trusted lieutenants, Senior Cabinet Minister Sunil Handunnetti, appeared on a popular television programme and effectively redefined bribery.

When confronted with questions about unexplained wealth in his asset declaration, he asked the journalist to take his complaint to court if he was so concerned about it. Handunnetti retorted that if someone gave him a gift and he accepted it, it should not concern anyone else. He went on to question the interviewer if he had a problem with it. Just hours later his boss was preaching about transparency and the need to fight corruption at the UN.

Critics were quick to pounce on the Minister’s logic and draw parallels with the infamous “Daisy Achchi” saga, where a bag of gems was allegedly delivered to the Rajapaksa household. The contention being, if the giver gave it gladly and the taker took it gladly, then why should it concern anyone? The Minister’s thinking seems more in-line with that of a rogue regime than one purportedly fighting corruption.

The Bribery Act is clear: any wealth a public official cannot explain can be confiscated. Yet, here was a Senior Minister openly mocking the law, normalising “gifts,” and daring journalists to challenge him. What was worse was the silence of the regime in response. No censure, no clarification, no disciplinary action. The silence spoke volumes. If a government that came to power promising clean hands now treats bribery as a matter of private arrangement, then what Sri Lanka is witnessing is not ‘system change’ but ‘system surrender.’

Independence compromised

More troubling still are allegations that the government has compromised the independence of the Bribery Commission. A former JVP heavyweight recently revealed on television that the newly appointed Director General of the Bribery Commission has been a long-time servant of the JVP. If true, it essentially compromises the credibility of an institution meant to stand above politics. How can the public trust investigations into corruption if the head is a political appointee? The fox, it appears, has been appointed to guard the henhouse.

When governments bend institutions to protect themselves rather than the public it amounts to state capture. The NPP once accused its predecessors of precisely this. But in just a year, it appears to have embraced the same playbook. The public is now left with the haunting question: is the Bribery Commission a watchdog or lapdog?

Assets and hypocrisy

The asset declarations of NPP ministers recently publicized by the Bribery Commission have raised further suspicion. Many have incomplete information: land owned without values declared, wealth left unexplained and even cryptocurrency holdings worth millions listed casually, despite the fact that crypto trading is illegal in Sri Lanka.

The Anti-Corruption Act requires that every asset be explained; how it was acquired, at what cost and how its value has changed. But these requirements have largely been ignored. One Minister had declared 44 perches of land but left blank how it was acquired. Another had listed over 100 perches of land at a valuation of Rs. 7,000.

In Singapore, the late Lee Kuan Yew dismissed his finance minister for accepting a free air ticket. In Sri Lanka, NPP ministers who have vowed to follow the Singaporean example redefine gifts and assets, and dare journalists to complain. One of the clearest symbols of this drift came earlier this year when President Dissanayake cut short a trip to Vietnam and returned to Sri Lanka on a private jet “provided by a well-wisher.” The government brushed it off as a harmless gesture. But symbolism matters; which is why Lee Kwan Yew did what he did. Freebies are how corruption often begins – not with sacks of cash, but with ‘gifts’ framed as generosity. Today it is a plane ride. Tomorrow it is a contract.

Empty words, full pockets

Beyond corruption, the government’s economic management has also raised questions. While in opposition, the JVP/NPP decried Sri Lanka’s debt levels, criticising ‘wasteful extravagance.’ They promised prudence. Yet in office, the same party is planning to borrow almost three times the cost of the original estimate to complete the first phase of the Central Highway. Such contradictions suggest that the NPP’s radical rhetoric in opposition is not matched by a coherent economic philosophy in government.

Dissanayake’s UN speech, in the final analysis, underscores a painful truth: it is easier to fight corruption and poverty with empty rhetoric than with concrete action. His words soared, but his government’s conduct stumbles. His ministers’ mock journalists, their asset declarations mock the law and his administration’s appointments mock the very idea of independent institutions. Ordinary Sri Lankans, already battered by inflation and disillusioned by decades of broken promises, feel betrayed once again. The people who promised to change the system are proving that the system has changed them.

Lessons from history

Sri Lanka has seen this cycle before. Each new government enters office with promises of reform only to succumb to the temptations of wealth and power. From the excesses of the UNP in the 1980s to the family rule of the Rajapaksas, reform has too often given way to rot.

What made the NPP different was its rhetoric of purity; its claim to stand outside this cycle. But if that purity is compromised in just one year, the consequences are unlikely to be promising.

If President Dissanayake wishes to salvage his credibility, he must act urgently and discipline his ministers by publicly censuring those who trivialize bribery. He must appoint independent professionals, not party loyalists, to watchdog institutions.

A year ago, Sri Lankans placed their hopes in Dissanayake and the NPP, believing they could deliver the long-promised but never-delivered ‘system change.’ Today, those hopes are hanging by a thread. At the UN, the President told the world that poverty and corruption must be defeated. Back home, his government is accused of deepening both. This contradiction must not be allowed to persist.

Leave a comment