By Dr. Charuni Kohombange

In the first epidemiological bulletin of 2026, released by the WHO’s South-East Asia Region (WHO SEARO) Office, health officials highlighted renewed concerns over the Nipah virus infection in India’s West Bengal State, sending ripples of concern across the region’s public health systems.

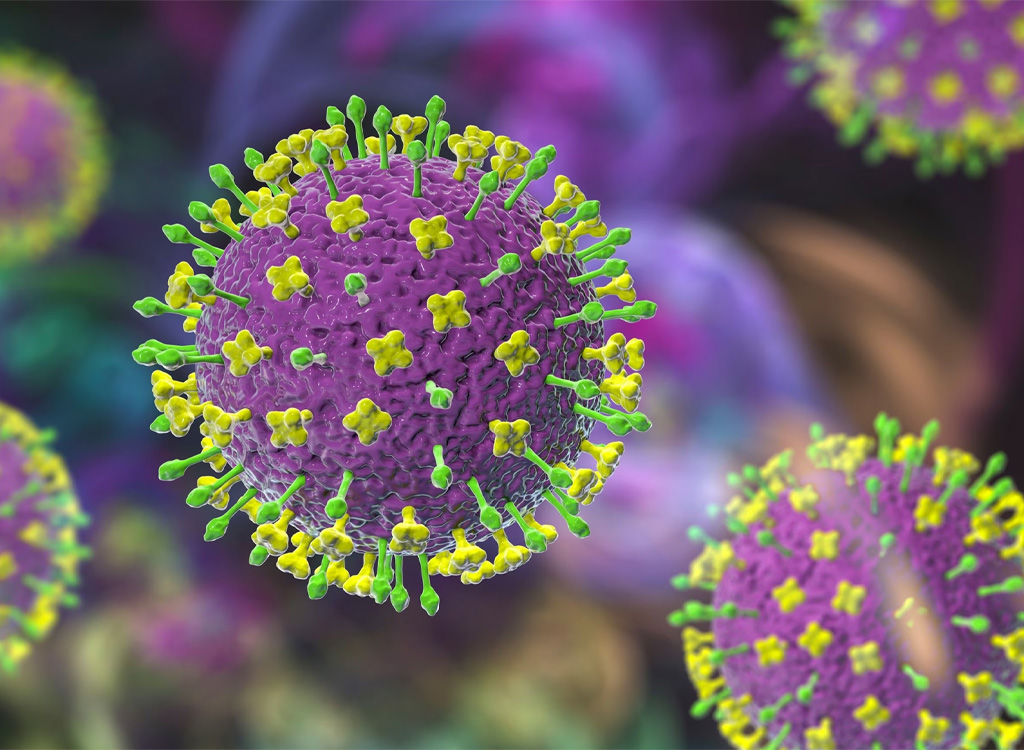

The Nipah virus is a zoonotic pathogen — one that can be transmitted from animals to humans — known for causing severe encephalitis (the inflammation of the brain, caused by an infection or an allergic reaction) and respiratory disease, with an alarmingly high fatality rate. Fruit bats of the Pteropus genus serve as its natural reservoir, though pigs and other animals can also act as intermediate hosts. Human-to-human transmission, while less common than animal-to-human spread, has been documented, particularly among family members and the caregivers of infected patients.

Latest situation: West Bengal cases reported

According to the WHO SEARO epidemiological bulletin covering the period from late December 2025 to mid- January 2026, two suspected Nipah virus cases were identified in West Bengal in early January. The infections were detected at the Virus Research and Diagnostic Laboratory of the Indian Council of Medical Research at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Kalyani, and preliminary investigations suggested possible exposure during a visit to the Purba Bardhaman District.

In response, the Indian Government quickly deployed a National Joint Outbreak Response Team to support containment efforts in West Bengal, intensify surveillance, trace and monitor high-risk contacts, and prevent further spread. While updates on the clinical status of the patients were limited in the publicly released bulletin, external media reports outside the WHO document, indicate that confirmed cases were later identified in the Kolkata and Barasat areas, affecting healthcare workers and prompting intensive contact tracing efforts.

This episode is significant because it marks the first Nipah virus cluster in West Bengal in nearly two decades, with previous regional outbreaks occurring in this Eastern Indian State in 2001 and 2007.

Why the Nipah virus commands global attention

The Nipah virus remains a pathogen of serious concern for the international health authorities for several reasons:

• High case fatality rate: Estimates from multiple outbreaks suggest that between 40 per cent and 75% of infected individuals may die, depending on the strain and the quality of care available.

• No licensed treatment or vaccine: Medical care for the Nipah infection remains supportive, focusing on managing symptoms and complications.

• Zoonotic reservoir and spillover risk: The presence of natural hosts such as fruit bats in many South and South-East Asian countries creates a persistent risk for spillover events, particularly where human–animal interfaces are common.

• Potential for human transmission: Although less efficient than airborne viruses like influenza, close contact with infected patients — as can occur in healthcare and domestic settings — can facilitate transmission.

Periodic Nipah outbreaks are not unprecedented. In the nearby country of Bangladesh, outbreaks tend to occur seasonally between December and April, often linked to the consumption of raw date palm sap contaminated by bats, and have resulted in annual infections for several years. The virus was first identified in 1999 during an outbreak among pig farmers in Malaysia and later recognised in multiple countries including Singapore, Bangladesh, India, and the Philippines.

Regional public health response

The WHO SEARO bulletin underlines the importance of rapid surveillance, outbreak investigation, and a coordinated response to such infections. The health authorities in India have scaled up surveillance in districts near the reported cases, implemented active contact tracing, and deployed specialised teams to manage the outbreak response.

Neighbouring countries, from Nepal to Thailand and beyond, have enhanced health screening measures at airports and borders to detect potential imported infections early, although the risk of widespread international spread remains low in the absence of sustained community transmission.

In Singapore, the Communicable Diseases Agency has stepped up vigilance by alerting hospitals to maintain heightened awareness for symptoms compatible with the Nipah infection, especially among travellers with recent exposure to the affected regions.

Balancing vigilance with context

Experts emphasise that while public concern is understandable — especially in the post-Covid-19 era — the Nipah virus behaves differently from pandemic-causing respiratory viruses. It is not as efficiently transmitted between humans, and past outbreaks have remained generally localised when caught early by public health measures.

The WHO continues to promote cooperation among countries for early detection and response, strengthening the laboratory capacity, and implementing effective infection prevention protocols. This includes guidance on identifying the early signs of the Nipah infection — such as sudden fever, headache, and encephalitic symptoms — and isolating suspected cases to protect caregivers and health workers.

The road ahead: Preparedness and research

The Nipah virus outbreak underscores the ongoing need for regional strategies to prevent and control emerging zoonotic diseases. The WHO South-East Asia Regional Strategy for Nipah virus prevention and control (2023–2030) outlines priorities such as surveillance enhancements, public awareness campaigns, and research into diagnostics and potential therapeutics.

Public health experts assert that rapid identification and containment remain the cornerstone of the response — paired with community education on reducing exposure to known risk factors, including contact with bats or the consumption of potentially contaminated foods.

Conclusion

The inclusion of the Nipah virus infection in the latest WHO SEARO epidemiological bulletin serves as a reminder that emerging pathogens continue to pose threats to global health. While the recent cases in India’s West Bengal have triggered heightened surveillance and caution, coordinated response efforts across South and South-East Asia aim to prevent escalation. As scientists work towards better tools for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, preparedness, vigilance, and transparent communication remain critical to managing Nipah and other zoonotic diseases in an interconnected world.

(The writer is a Medical Officer at the National Blood Transfusion Service)

Source: The Morning

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of this publication.

Leave a comment