By Prof. Prasanna Perera

The Context

Sri Lanka entered an International Monetary Fund (IMF)-supported debt restructuring programme in 2023 following the 2022 sovereign default under Mr. Ranil Wickramasighe’s presidency. The Extended Fund Facility (EFF) aimed at restoring macroeconomic stability through fiscal consolidation and structural reforms to achieve medium-term external viability and debt sustainability.

IMF reports (2025) had projected public debt at 104.6% of GDP by 2026, with external restructuring nearing completion. Gross Financing Needs before the announcement of bankruptcy, from 2013 to 2022, were 23% of GDP, and this is expected to remain at 13% of GDP per annum.

While certain macroeconomic indicators showed partial improvement, such as the return to a primary surplus of 2.0 percent of GDP in 2026, the economy remained fragile. Real wages, employment levels, poverty rates, and GDP have not recovered to their pre-crisis levels of 2019, leaving Sri Lanka vulnerable to external shocks. This fragility was starkly exposed by Cyclone Ditwah in late 2025, alongside recurrent floods and landslides, which significantly worsened poverty, housing insecurity, and fiscal pressures.

On December 19, 2025, the IMF approved SDR 150.5 million (US$206 million) under the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI), to be repaid over 3-5 years. These funds will support disaster response, essential services restoration, and infrastructure repairs.

Using World Bank data, IMF macro-fiscal indicators, I argue that Sri Lanka requires a renewed debt sustainability arrangement to align debt obligations with post-2025 realities. This analysis supports SJB Leader Mr. Sajith Premadasa’s repeated appeal to the NPP Government led by JVP to enter a new deal with IMF and lenders.

Debt sustainability and IMF fiscal indicators

According to the IMF (2024), Sri Lanka’s public and the state guaranteed debt peaked at 126.3% of GDP in 2022. Despite restructuring agreements, the debt ratio is projected to remain above 100% of GDP through 2028. The IMF forecasts a gradual decline under strict fiscal discipline, targeting a debt stock of 95% of GDP by 2032. However, these projections assume no major exogenous shocks to the economy.

Sri Lanka has achieved a primary surplus of 2.2% of GDP in 2024 and is projected to achieve 3.4% of GDP in 2025 and 2.0% of GDP in 2026, meeting IMF performance criteria (IMF, 2025). However, I have doubts about the primary account balance data because a significant portion of domestic debt to the local contractors and suppliers is ignored when calculating this. Anyway, the IMF emphasizes that primary surpluses alone do not guarantee debt sustainability when gross financing needs remain elevated, and growth is vulnerable to shocks. Even after restructuring, interest payments are projected to absorb around 25–30% of government revenue in the medium term (IMF, 2024).

Cyclone Ditwah fundamentally altered these assumptions and made IMF targets and forecasts unrealistic. Reconstruction spending, emergency relief, and revenue losses from disrupted economic activity directly weaken the debt sustainability path envisaged in the IMF baseline.

Poverty and vulnerability: What the World Bank says

Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa has emphasized the need to amend the IMF programme. Given the harsh economic realities facing ordinary Sri Lankans, his calls for program modifications that are not only justified but essential.

The World Bank defines extreme poverty as income below $4.2 per day. Sri Lanka’s extreme poverty stands at 22.4% in 2025, with forecasts indicating this could exceed 30% by 2027, as an additional 10% risk of falling into extreme poverty. Some estimates suggest up to 40% live below the poverty line.

Multidimensional Poverty Index analysis from CGIAR shows 24.5% of Sri Lankans are multidimensionally poor, with 50% facing multidimensional vulnerability, with significant hardship in estate and rural areas, with health (nutrition, child mortality) and living standards (basic services, assets) as major deprivation areas.

Major contributing factors include the economic crisis, causing household poverty and declining incomes, persistently high food prices forcing families toward cheaper, less nutritious options, structural issues such as income inequalities and inadequate social protection, and climate-related disasters.

Then, the most important thing is that the World Bank prepared all the poverty and other indicators before Cyclone Ditwah.

Cyclone Ditwah has caused an estimated US$ 4.1 billion in direct physical damage to buildings and contents, agriculture, and critical infrastructure, according to a World Bank Group Global Rapid Post-Disaster Damage Estimation (GRADE, 2025). This damage is equivalent to about 4 percent of Sri Lanka’s GDP. About two million people have been affected by this cyclone. About 500,000 families have been severely damaged. These estimates significantly underestimate the total economic impact, as they exclude indirect costs such as disruptions to the tourism industry and losses to the livelihoods of the public.

The cost of meeting minimum basic needs has more than doubled. In 2021, a person required LKR 7,913 per month to cover essential expenses. Now, this figure has surged to LKR 16,303.

The housing crisis reveals the scale of vulnerability. Before the cyclone, there were 160,000 line rooms across the country. More alarmingly, one million people, approximately 15% of the population, lack permanent shelter.

Additionally, youth unemployment has become a serious concern, with more than 20% of young people unable to find work. Countless families struggle to pay their electricity and water bills, exacerbated by Cyclone Ditwah.

In response to the devastation caused by Cyclone Ditwah in December 2025, over 120 international development economists, including Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, inequality expert Thomas Piketty, and MIT economist Jayati Ghosh, have called for the immediate suspension of Sri Lanka’s external sovereign debt payments and a comprehensive new restructuring plan. Their demands center on three key areas: an immediate halt to all external sovereign debt payments, a new debt restructuring framework that ensures long-term sustainability and recognizes climate-driven disasters as systemic shocks, and significant debt cancellation without punitive conditions to free up resources for disaster recovery, social protection, reconstruction, and development. The economists emphasized that even under the IMF’s own projections, the previous debt deal gave Sri Lanka a 50% probability of default or requiring another restructuring, making the current crisis foreseeable rather than unexpected.

I would like to ask what the government’s stance is on this matter.

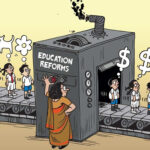

Also, what is the benefit of the IMF-led economic model that the government is following in the face of these acute economic problems revealed by the World Bank, which is the IMF’s sister organization?

Why is renewed debt restructuring economically justified?

Based on IMF, and World Bank evidence, renewed debt restructuring is justified because:

• Debt sustainability assumptions are no longer held after a large-scale natural disaster.

• High poverty and vulnerability constrain the social feasibility of continued fiscal tightening.

• Housing and reconstruction need demand sustained public investment, not short-term emergency financing.

• Cost-of-living pressures reduce real income, undermining human capital accumulation.

• Preventive restructuring is less costly than future defaults, as emphasized in IMF debt frameworks.

• Debt restructuring is therefore not a repudiation of reform, but a necessary recalibration to new economic realities.

• IMF press release No. 25/235: “The economic outlook is positive, but downside risks have increased. In case shocks materialize, the authorities should work closely with the Fund to assess the impact and formulate policy responses within the contours of the program. Steadfast program implementation will be crucial.”

The economy is expected to grow by 2.9 % in 2026, and the real growth rate, according to IMF, will be 3.1% even in 2027. According to IMF estimates, Sri Lanka expects to have US$ 14.2 billion or reserves to cover 6 months of imports to the country. Despite progress in debt restructuring negotiations, the external shock of Cyclone Ditwah has created grounds for renegotiation with multilateral and other lenders, as repeatedly urged by Opposition Leader Mr. Sajith Premadasa to secure a fairer deal that protects the poor and middle class from excessive tax burdens.

(The writer is a senior Professor at the University of Peradeniya)

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the official position of this publication.

Leave a comment