By Dr. Jehan Perera

A prominent feature of the first year of the National People’s Power (NPP) Government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which were expected of it. It has also not abused power, or its two-thirds majority in the Parliament to benefit itself, in the manner that previous Governments did. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the Government was elected and the high expectations that have accompanied its rise to power. When in the Opposition and in its Election manifesto, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) and the NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on Constitutional reform that included the abolition of the Executive Presidency, the strengthening of independent institutions, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act as amended (PTA) and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five per cent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the Government with a 2/3 majority in the Parliament is a testament to the faith the general population placed in the JVP-NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988–1990 period of the JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP Parliamentarians engaged in debate with well-researched critiques of Government policy and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanised citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

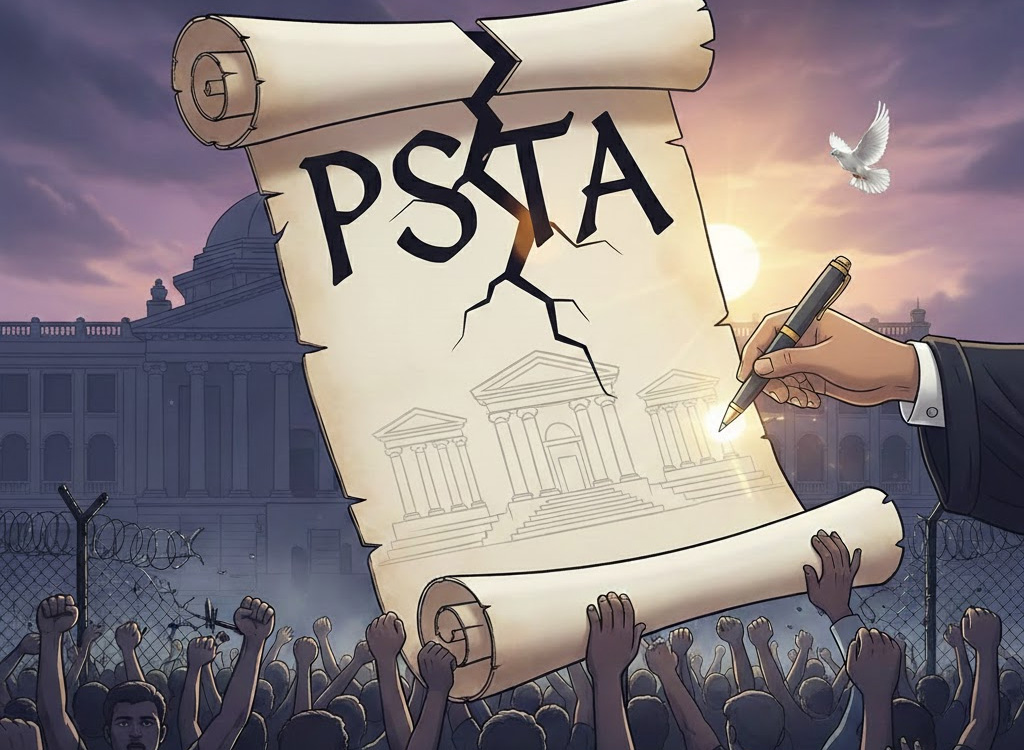

In this context, the long delay to repeal the PTA, which has earned notoriety for its abuse, especially against ethnic and religious minorities, and now the bid to replace it with another, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights (HR). The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-State which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the 1988 to 1990 period. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December of last year (2025), is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter-terrorism bills.

Public discussion

What distinguishes this moment from previous ones is the level of public awareness and civic engagement that now exists. The Aragalaya demonstrated that Sri Lankans are no longer passive recipients of State power but active participants in shaping it. A law as important as the PSTA, one that can profoundly affect civil liberties, political dissent, and the balance of power between the citizen and the State, cannot be enacted without broad public discussion.

The Government’s decision to allow two months for public comment is therefore welcome, but, consultation must be meaningful, not cosmetic. Given Sri Lanka’s long and painful experience with national security legislation, this consultation period will provide a valuable opportunity to prevent the repetition of past mistakes.

Meaningful public engagement prior to the enactment of a new anti-terrorism law is essential if the promise of system change is to be realised and if Sri Lanka is to avoid entrenching yet another draconian law whose consequences will be felt for decades to come. Civil society groups and legal experts have begun analysing the draft law. Their concerns echo those raised over decades: vague definitions, excessive Executive discretion, and weak judicial oversight. Despite its stated commitment to the rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PSTA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. The Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed that, “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years.” HR lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned the broad definition of terrorism, “empowers State officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as terrorism.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against the abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the Government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates they tend to become tools of routine governance. The Government also needs to be cognisant that national security laws are notoriously difficult to get rid of once in place, like the PTA, which was said to be for six months and has lasted 46 years.

Debate matters

The value of public discussion is that it forces those who make laws and policies to justify each clause, power, and safeguard. It compels transparency. It also ensures that the voices of those most vulnerable to abuse, minorities, activists, journalists, and political opponents, are heard. It also strengthens the legitimacy of the final law, whatever form it takes. Countries that have successfully reformed national security legislation, such as South Africa after the apartheid, did so through extensive public consultation. Sri Lanka cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the past by rushing through a law that concentrates power without adequate checks.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant, especially where financial accountability and non-corruption is concerned. The Government leadership appears to take the position that they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those that they have confidence in. It may also underlie the Government’s approach to its replacement of the PTA, strong in the confidence that no abuse will take place under their watch. Yet, this approach carries risks. Leaders and governments are not permanent.

Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP Government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, for which reason the people voted for them. The PSTA debate offers the Government a chance to demonstrate that it is serious about system change not only in rhetoric but in practice. By embracing public consultation, revising problematic clauses, and ensuring strong judicial oversight, the Government can set a new standard for democratic lawmaking.

The two-month consultation period on the PSTA therefore carries special responsibility. The National Peace Council (NPC) organisation urges civil society organisations, the legal community and in particular the Bar Association to study the draft law carefully, to draw on Sri Lanka’s experience and international standards, and to place their considered views before the Government to incorporate in a well-balanced law. These would include provisions for speedy judicial actions to release those improperly and unfairly arrested under its provisions and compensation to those who are discharged without legal action after many months or years. Such protective features need to be built into the laws and institutions that govern the country.

(The writer is the Executive Director of the NPC organization)

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of this publication.

Leave a comment