A dangerous double standard

By Vox Civis

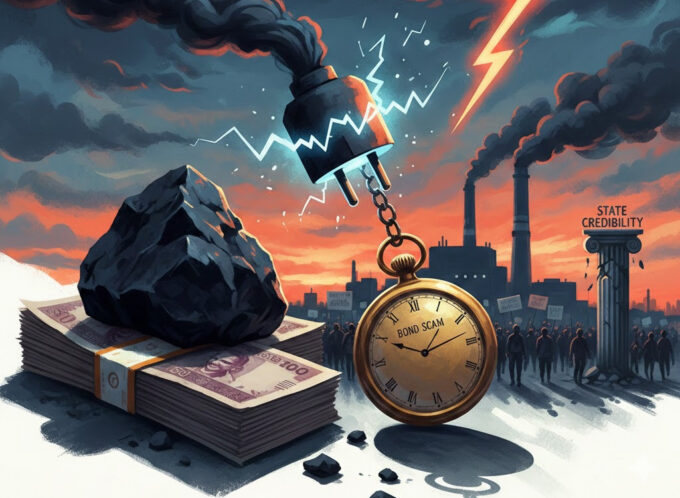

One thing the National People’s Power (NPP) government has demonstrated with remarkable consistency during the year and four months it has been in office is a truth Sri Lankans know all too well: that what is sauce for the goose is very rarely sauce for the gander. The promise of “system change,” delivered with moral certainty and revolutionary fervour that swept the four corners of this island nation, has slowly but unmistakably given way to the familiar and troubling reality of the old dual system of governance, where accountability is relentlessly pursued when it suits the ruling establishment and quietly suspended when it threatens to turn inward. Taken together with the continuing economic model/policies of the previous era, nothing – if at all – appears to have changed despite the lofty promise of change that propelled the NPP to office.

Given the litany of broken promises of the past, this state of affairs cannot simply be discounted as yet another story of political hypocrisy, for the profound reason that the roots of this ‘change’ accrue to a historic event – a people’s revolution also known as the ‘Aragalaya,’ which set the stage for ‘system change.’ A concept which then was literally hijacked by the NPP, resulting in it sweeping the electoral map at the subsequent hustings.

The NPP does not appear to realise that this profound hunger for change never really changed, but was only momentarily withheld to provide space for the party to settle in office. But that window is now long gone, and what remains is the same old discontent about a system that works for some and not for others. What persists is the same old story about the corrosion of institutions, the weaponisation of law, and the dangerous precedent set when a government that rose to power on the promise of ethical rectitude begins to mirror the very abuses it condemned.

Claim to legitimacy

The NPP did not inherit a blank slate; it inherited a country exhausted by selective justice, politicised prosecutions, and institutions bent to serve power rather than principle. Its central claim to legitimacy was that it would break this cycle. What is now becoming evident is that the cycle is not being broken, but rather, being repurposed.

From the earliest months of its tenure, scandals began to surface with an unsettling regularity. These were not fundamentally different from those that plagued previous administrations. What differed was the response. Where similar allegations in the past were held up as proof of endemic corruption and moral decay, comparable controversies under the NPP banner have been minimised, rationalised, or quietly shelved.

At the same time, the machinery of investigation itself has been politicised to unprecedented levels that it has made past administrations actually look good. Never in the past did the ruling parties invade the bureaucracy to the extent of appointing party henchman to posts such as Secretaries of key Ministries or even as Head of the Criminal Investigation Department of the Police, but that is exactly what has taken place under the very regime that promised ‘system change.’

Consequently, prosecution and public vilification have become notoriously one sided – turned with renewed zeal against political opponents but none against the ruling entity despite a growing list of misdemeanors, including allegations of grand corruption.

Nowhere has this double standard been more starkly exposed than in the continuing attempts to prosecute former President Ranil Wickremesinghe. What was presented to the public as a righteous pursuit of accountability has, beneath the surface, revealed a disturbing tale of internal dissent, professional resistance, and alleged pressure within the state prosecutor, Sri Lanka’s Attorney General’s Department.

Internal dissention

Local media reports have detailed an extraordinary disagreement within the Department over whether there is sufficient evidence to sustain criminal charges against the former President regarding the alleged misappropriation of Rs. 16.6 million in public funds during an overseas visit. According to these reports, Deputy Solicitor General Wasantha Perera, who supervised the Criminal Investigation Department’s probe, reached the clear conclusion that the evidence simply did not meet the threshold required for prosecution. His findings, contained in a detailed six-page report to Attorney General Parinda Ranasinghe, are said to have pointed out fundamental flaws in the investigative process itself.

Among these was the assertion that the former President’s travel route via Britain was standard procedure when returning from Cuba via New York, irrespective of any invitation from the University of Wolverhampton. More troubling still was the revelation that the CID team that travelled to the United Kingdom to verify the authenticity of the alleged invitation letter had supposedly done so without obtaining the necessary authorisation under the Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters Act. This procedural failure reportedly prevented the team from even recording an official statement from the British authorities, a glaring omission that would undermine any prosecution in a court of law.

Perera’s supposed conclusion has been unambiguous to the extent that in the absence of evidence to establish the primary offence, there could be no case for aiding and abetting against former Presidential Secretary Saman Ekanayake. That such a conclusion could provoke controversy rather than closure, speaks volumes about the climate in which these investigations are being conducted.

On the other side of this internal divide stands Additional Solicitor General Dileepa Peiris, the chief supervising officer of the investigation, who reportedly maintains that charges can indeed be filed based on the existing material, a view apparently supported by CID investigators. The fact that senior law officers within the same department can reach diametrically opposed conclusions is not, in itself, unusual. What is unusual and in fact deeply troubling is the allegation that professional disagreement has escalated into pressure so intense that officials have resigned, sought transfers, or stepped aside from politically sensitive cases.

While this state of affairs can in no way be described as suggestive of a process seeking accountability, a more appropriate description is ‘prosecutorial adventurism,’ driven by political necessity rather than evidentiary sufficiency. It undermines the very foundations of the rule of law and sends the chilling message to public officials that independence will be tolerated only so long as it aligns with the political objectives of those in power.

A different story

And yet, while extraordinary energy has been expended attempting to construct cases against former leaders, an altogether different approach has been taken when allegations of waste and mismanagement point directly at the current administration.

The ongoing controversy surrounding the Grade Six education reforms has laid bare this contradiction in the starkest terms. Here, prima facie evidence exists of massive wastage of public funds, procedural recklessness, and a complete disregard for stakeholder consultation; the very sins for which the NPP has consistently crucified its predecessors.

By all accounts, the reforms have been conceived and implemented within the confines of the Ministry of Education without meaningful engagement with teachers, academics, parents, professional bodies, or even Parliament which was taken by surprise when the reforms were announced. Modules have been prepared, printed and distributed at enormous cost, only for their implementation to be abruptly deferred following public outrage over content errors, including an inappropriate web reference in a Grade Six English textbook.

The financial implications are staggering. The Ceylon Teachers’ Union has stated that nearly Rs.1 billion has already been spent on the reforms, with additional funds now required to review, amend, and potentially reprint material that may no longer be usable. This in no way can be categorized as a marginal governance error. Put simply, it is a colossal waste of taxpayer money at a time when Sri Lanka remains economically fragile and every rupee is hard-won.

Predictably, the main opposition party has begun to ask the obvious questions. The Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) has raised the possibility of lodging a complaint with the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC), citing losses incurred through a reform process conducted, in their words, behind closed doors. Parliamentarian Rohini Kavirathna has been particularly forthright, pointing out that funds spent on printing and distribution came directly from the public purse and that those responsible must be held personally accountable.

The deeper malaise

Her criticism cuts to the heart of the matter. Sri Lanka undoubtedly needs education reform. But reform conducted in secrecy, without consultation, parliamentary oversight, or professional consensus, is not reform and more like administrative arrogance. Kavirathna’s observation that even the Sectoral Oversight Committee of Parliament was bypassed underscores the deeper malaise of a governing culture that confuses electoral victory with a mandate for unilateral decision-making.

She has also raised serious concerns about the National Institute of Education (NIE), the institution entrusted with shaping the intellectual future of the nation. If, as alleged, unsuitable individuals occupy key positions within the NIE, then the resulting decline in quality is not an accident but an inevitability. The resignation of the NIE’s Director-General pending investigation and the admission that at least 18 professionals failed to flag the problematic content, point not to an isolated oversight but to systemic failure.

Yet, despite these admissions, despite the Prime Minister and Education Minister herself describing the episode as a “grave error,” there has been no visible rush to summon investigators, no public spectacle of arrests, no breathless media briefings about imminent indictments. Instead, there has been deferral, review, damage control and half-hearted assurances of an investigation.

The Cabinet decision on January 13, 2026, to postpone the Grade Six reforms until 2027 is being framed as a gesture of sensitivity to parental concerns. Cabinet Spokesperson Dr. Nalinda Jayatissa explained that the government was “not ready to continue education reforms with even the slightest doubt among parents.” While this may be commendable in tone, it does nothing to address the fundamental question of accountability for resources already expended.

Profound political fallout

The political fallout has been significant. Calls for the resignation of Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya have grown louder, with discussions of a no-confidence motion gaining traction. The controversy has also been weaponised in broader culture wars, with critics reviving attacks on her past advocacy positions. Meanwhile, public protests have fractured along familiar lines, with some parents demanding a complete halt and others urging the release of non-controversial modules to prevent students from falling behind.

Lost in this noise is the central issue: whether the same standards applied so aggressively to political opponents will now be applied to those in power.

This is the real test of the NPP’s claim to moral superiority or the ‘system change’ it promised. It is not whether mistakes occur – no government is immune to error – it is whether those mistakes trigger the same institutional reflexes that are activated when the accused sit on the opposition benches. Will investigators be unleashed with the same fervour? Will files be dusted off, travel scrutinised, procedural lapses magnified, and resignations extracted? Or will accountability quietly dissolve into collective amnesia?

Sri Lanka has been here before. Governments that begin by promising justice often end by practicing selectivity. Institutions that should act as impartial arbiters are reduced to instruments of political convenience: to make matters worse, never to this extent. The tragedy is not merely that this happens, but that each repetition further erodes public trust, making genuine reform ever more difficult.

The NPP still has a choice. It can acknowledge that the credibility of its anti-corruption agenda depends not on how fiercely it pursues yesterday’s rulers, but on how honestly it confronts its own failures today. It can allow institutions to function without fear or favour, even when the findings are politically inconvenient. Or it can continue down the familiar path, where accountability is a weapon wielded outward, never inward.

If it chooses the latter, then the promise of ‘system change’ will join the long list of slogans that inspired a weary nation and then quietly betrayed it. And Sri Lanka, once again, will be left to grapple with the consequences of a truth it knows too well: that justice, when applied selectively, ceases to be justice at all.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of this publication.

Leave a comment